More On: Europe

Just say no to the new war that won't end

A Crisis Made in the World

How to Keep from Starting a New Cold War in a Multipolar World

Ukraine is moving into a new dark age of drone warfare

Meta disables Russia's network of propaganda aimed at Europe

The Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Bold, was a fighter's warrior. Philip had been a soldier since he was a boy, hawk-nosed, ambitious, and aggressive. When he fought with his father, King John II of France, at the battle of Poitiers in 1356, he was still a smooth-faced 14-year-old child. When Edward, the Black Prince of Wales, defeated the French on the field at Poitiers, he, like King John, was taken prisoner by the English. A decade later, the duke, always seeking for a method to gain an advantage over the English invaders, welcomed a fresh technology: gunpowder.

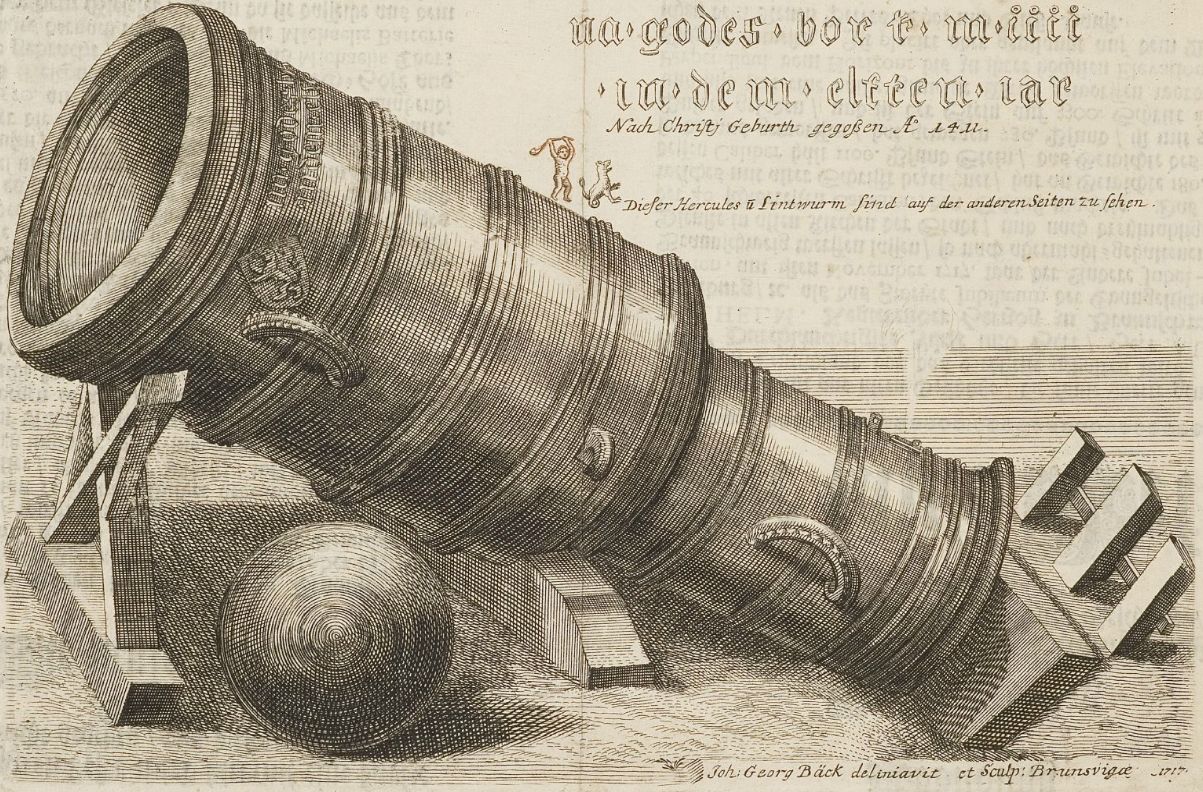

But Philip the Bold recognized potential in the new weaponry, particularly the massive siege guns called as bombards, and began investing extensively in them in 1369. The Hundred Years' War (1337–1453) was then a series of on-again, off-again dynastic battles between France and England. When King Charles V of France, Duke Philip's brother and sovereign, ordered him to fight the English in the Calais region in 1377, the duke responded by sending more than 100 new guns, including one monster of a gun that discharged a stone bullet weighing 450 livres (around 485 pounds).

The English-held fortress at Odruik, which was built with solid brick walls and encircled by a thick layer of outworks, was one of the duke's intended objectives. Odruik is a difficult nut to crack. Even when the duke's forces prepared to deploy their massive siege gun in plain view of the castle walls, its defenders seemed to think so as well, and were optimistic that they could hold out against Duke Philip's army.

The first few bullets from Philip's siege-battery blew the outer walls of Odruik to smithereens. Soon, stone cannonballs were flying through the walls as if they didn't exist, and the outer walls were no longer there. After Philip's cannons had fired a total of around 200 rounds, most of Odruik's once-proud walls were in ruins, and Odruik's defenders capitulated before the duke could send his soldiers through the gap and into the castle.

The victory of Philip the Bold at Odruik in 1377 was a foreshadowing of things to come, revealing unpleasant realities. Gunpowder artillery had previously been utilized in sieges, but Odruik was the first time it had won a decisive victory against a stronghold. The siege of Odruik revealed that cannon were more powerful than any siege machine yet created, and could take down castles in a matter of hours if the cannons were big enough and there were enough of them. Throughout the rest of the Middle Ages and beyond, what happened at Odruik would be duplicated at castles across continental Europe and the British Isles.

Gunpowder began to have an impact on the conduct of battle in the West during the next century, with improved siege artillery making the difference between success and failure in ground combat. In the last stages of the Hundred Years' War, the French would use artillery to push the English off their land, converting loss into victory. Christians in Iberia would use artillery to force the Moors out of their last strongholds in Granada, resulting in the birth of Europe's first superpower: Spain. In 1453, the Ottomans, who were also keen students of gunpowder artillery, would employ their gigantic bombards to demolish the remaining traces of the Roman Empire by breaking down the walls of historic Constantinople.

After Odruik, artillery would spell both the end of the castle and the emergence of a new kind of warfare, based on firepower, that relied on the massed use of gunpowder weapons for siege, on the battlefield, and at sea. Within a century and a half of Philip the Bold’s quick and noisy victory, very little about European warfare would even vaguely resemble what had come before. The weapons, the size and organization of armies, the role of fighting men and leaders—even the sounds, the smells, and the scale of the European battlefield—would be radically transformed by the advent of gunpowder weaponry. And the implications for life beyond the narrow horizons of the battlefield were even more profound.

Artillery meant the end of the castle, an edifice that both symbolized the independence and power of local warlords in medieval Europe and gave those warlords a means of resisting the encroaching ambitions of central governments embodied in Europe’s emerging dynastic monarchies. The cannon took down the autonomy of the old warrior aristocracy just as it did the walls of their castles; the onerous expense of making and maintaining cannon meant that only the wealthiest lords—the monarchs themselves—could afford to build up their arsenals of these terrifying new weapons. The cannon, in short, concentrated military force and political authority in the hands of the state at the expense of noble warlords.

What made artillery possible was gunpowder, and gunpowder was the single greatest invention of the European Middle Ages, even if it wasn’t actually European. It was first developed in China as early as the ninth century AD, and over the intervening centuries the Chinese had become proficient in its use. They employed the substance as an incendiary at first, only later discovering that it could also be used as an explosive and as a propellant, two related but distinctly different roles.

Just when gunpowder first came to Europe, and how it did so, remain mysteries. It may be that the Mongols, who used gunpowder weapons, unwittingly passed it along during one of their incursions into Europe’s eastern borderlands in the 13th century.

In his treatises Opus Majus and Opus Tertium (about 1267), English scholar Roger Bacon mentions gunpowder, and a German monk called Berthold Schwarz, who is possibly mythological, has been credited with performing early tests with the chemical. It doesn't really matter in the end. Disputes about the origins of gunpowder, like most historical disagreements over "who accomplished what first," end in a stalemate. To summarize, the Chinese originated and pioneered the use of gunpowder; Europeans received it in some form from the East, and their use of it developed independently of Asia.

From the time of its first use in the Middle Ages until its replacement by better propellants and explosives in the 19th century, gunpowder went through a continual process of reinvention and reformulation. Its basic composition, however, remained the same throughout: roughly 75 percent saltpeter (potassium nitrate), 15 percent softwood charcoal, and 10 percent sulfur, by weight.

Gunpowder, often known as black powder, is neither an ideal explosive nor a reliable propellant. Black powder was initially a simple concoction made by mixing the three components using a mortar and pestle. The chemical is very flammable and may be quickly ignited by a spark or flame. However, it may be made neutral just as easily: water, even excessive humidity, can render it worthless.

Gunpowder doesn’t actually explode when ignited. Rather it deflagrates—it burns rapidly—which means that it is better suited to its propellant role than to its role as an explosive. Black powder burns much faster than modern smokeless powders, and when used as a propellant with a projectile, it produces lower velocities than modern, slower-burning powders do.

Black powder also burns inefficiently, producing two undesired byproducts when ignited: smoke and fouling. Burning black powder generates clouds of noxious white smoke, enough to reveal a shooter's position with a single shot and to impair visibility when fired from a large number of guns. When black powder is burned, it produces hard carbon soot. Fouling, as this residue is known in weapons, can have significant effects. Long-term black powder fire in a gun barrel will deposit layer after layer of fouling, progressively restricting the inside of the barrel (the bore) and making loading difficult, if not impossible.

Gunpowder may not have been an ideal propellant or explosive, but in 1400 it had no competitors, and for all its faults it was effective enough. It would not have to wait very long for a military application.

That application was the practice of siege warfare. No form of land-based combat has been more commonplace than the siege, throughout the sweep of human history from the earliest known wars to the investment of Leningrad in 1941–1944. Pitched battles between armies or navies attract more attention, for they are suited to storytelling: battles are concise, they have movement instead of stasis, they have a narrative arc—battles are the stuff from which high drama is wrought. Yet the siege, for all its mechanical drudgery, is universal. Before the 20th century, the siege was the principal kind of hostile interaction between opposing armies, and was far more common than the pitched battle. Sieges were also costlier, consuming more resources—men, materiel, and time—than pitched battles.

The castle was the primary site of siege in the Middle Ages. In the ninth century, castles first appeared in Europe, rising among the shattered ruins of Charlemagne's dominion. Castles, as fortified houses of strong lords, became inextricably related to and emblematic of the feudal system that dominated so much of Western European social and political life. Castles served as local authority and judicial centers, as well as a way of managing and safeguarding the settlements that sprung up around them. They could serve, also, as focal points for rebellion. For a willful vassal who did not feel inclined to obey his lord or king, a castle was a sanctuary and a power base. In the emerging kingdoms of the High Middle Ages, castles strengthened the power of the noble landowning class, often at the expense of royal power.

In summary, castles had an importance that extended well beyond their military duty, yet they were first and foremost fortresses. The Crusaders' huge castles, such as the magnificent Krak des Chevaliers in Syria, allowed European invaders to have a near-constant presence in the Holy Land, protect the fragile Crusader nations, and launch offensive operations. The construction and holding of castles were important to English military activities in France during the Hundred Years' War. The design of the fortress, like any technology with a centuries-long useful life, was continually developing. The motte-and-bailey fortifications of the 10th century would seem puny and impotent when compared to the stone-built castles of the 13th.

From a military aspect, the castle was a long-lasting technology because it was effective at its primary function: keeping enemy troops out and keeping the people within secure. High walls and fortified gates deterred forcible access; brick walls were fireproof; and towers with loopholes—thin vertical shooting slits for archers—provided a measure of protection, making a besieging army's approach potentially expensive. A castle might hold out forever if the defenders were well-supplied and had convenient access to water. For a besieging army, if a castle could not be taken by storm, or its garrison intimidated or starved into capitulation, then it would have to be reduced.

Reducing a castle was an uncomplicated process, and quite literally mechanical, in the sense that it involved the use of machines or siege engines. While it was possible to bring down an outer wall by sapping—that is, by tunneling under the very foundations of the castle, causing the walls to sink and hopefully to collapse—breaching a wall by means of siege engines was the preferred method. Medieval siege engines, or “mechanical artillery,” had changed little since late antiquity: a mechanical force—torsion in catapults, counterweights in trebuchets, and human brawn in onagers—powered a heavy throwing arm that could hurl a heavy projectile, like a large stone, and send it crashing against the castle’s outer walls. Though simple in concept, the act of smashing walls with such weapons was laborious and time-consuming. It could be costly in lives, too, if the crews operating the machines were exposed to archery, which was likely because the range of catapults and trebuchets was quite short. A heavy trebuchet could not toss a large stone much further than 200 yards, within effective longbow range. Consequently, the results were often long in coming.

This is where gunpowder came in, but not as an explosive— which, perhaps surprisingly, was almost an afterthought. It wasn’t until late in the 15th century that European soldiers began to use gunpowder in so-called mines: massive quantities of gunpowder packed in tunnels dug beneath the castle walls. When detonated, such subterranean mines could collapse the sturdiest wall in moments. Instead, gunpowder found its first serious employment as a propellant in a primitive gun. That technology—compressing a charge of gunpowder in a tube that was closed at one end and open at the other, so that the expanding gases from the deflagrating powder would push out a projectile with great force and speed—was also a Chinese invention. In Europe, when gunpowder arrived, the knowledge of primitive firearms arrived with it.

The first significant employment of firearms in the West was with genuinely large cannons, known as gunpowder artillery. This may appear to be paradoxical. Small should, therefore, come before enormous. However, small armaments, like as handguns, were eventually added to the European arsenal. Cannons were the first weaponry to be used in the West.

A cannon, or bombard, might seem like the simplest of weapons, but in the Middle Ages metallurgy and metalworking had not yet advanced to the point where it was possible to cast a large tube in one piece, at least not in any metal sturdy enough to withstand the shock released by the deflagrating gunpowder. The first cannon were of “hoop-and-stave” construction, products of the cooper’s art rather than the iron-founder’s. Long wooden staves were laid together in parallel around a central core, and were then bound together and reinforced by hoops of wrought iron. Soon iron bars replaced the wooden staves. The resulting tube was open at both ends, and so the first European cannon were breechloaders—the powder and projectile were loaded not from the muzzle, where the projectile exits the barrel, but from the opposite end. A separate breech-piece acted as a powder chamber; it was attached to the open breech-end of the tube, and was then secured in place with a wooden wedge.

There was not much about such a weapon to inspire confidence. Even ignoring the many serious deficiencies of gunpowder, the cannon themselves had plenty of problems of their own. Hoop-and-stave construction is inherently weak. The earliest pieces burst frequently, and were nearly as dangerous to their gun crews as they were to their intended targets. And because it was impossible to create an airtight seal between the open-ended tube and the breech-piece, there would always be a gap between the two. Hot gases would leak from the gap when the gun was fired, bleeding off some of the energy of the deflagrating powder and potentially burning anyone unwise enough to stand close to the gun.

These early gunpowder monsters were crude weapons, to be sure, and their performance reflected it. In all the ways that we assess firearms—range, accuracy, rate of fire, reliability—the bombards came up short. But in the 14th century, there was simply nothing better to which they could be compared. Their range was limited, but they needed only to outrange an arrow or a crossbow bolt so that their crews could work safely outside arrow range. Their accuracy was poor, but their targets were anything but small; they needed only to be able to hit the towering outer walls of a castle. Their projectiles flew slowly, but they only needed enough force to shatter brick or stone masonry. They were slow to load and fire, but siegecraft demanded patience, not speed.

In short, to justify its existence and the not-inconsiderable sums of cash and materials that it consumed, gunpowder artillery only had to be better and faster at smashing castle walls than the catapult and the trebuchet. Even in its earliest, crudest, most primitive forms, the bombard met those criteria. Besides, the catapult and the trebuchet were the late-generation offspring of a venerable, mature technology, at the apex of their potential, unlikely to be improved upon. Gunpowder was yet in its infancy. There was nowhere for it to go but up.

And up it went. Between the mid-1300s and the early 1500s, gunpowder artillery advanced rapidly, or as rapidly as any technology would before the modern era. During this period, cannon would assume most of the characteristic features that would carry the weapon through to the 19th century. Advances in metallurgy and the metal-founder’s craft account for most of those advances. European artisans learned to cast cannon out of iron and bronze—solid, in one piece, much as church bells were cast. Bronze, an alloy of copper and tin, was the preferred material; cast bronze wore better and longer than cast iron, and cast-bronze cannon were thought to be less prone to bursting when fired. Cast iron, on the other hand, was cheaper and slightly less dense. The two materials would predominate in artillery manufacture until the advent of mass-produced steel, later in the 19th century.

The greater expense of cast-metal cannon tubes was worth the investment. They were infinitely more stable than the early hoop-and-stave guns. That was a great advantage in itself, but there was more to it. Solid-cast cannon had to be loaded from the muzzle, since the cast gun would by definition be closed at the breech-end. Powder and projectile would have to be inserted from the muzzle and then rammed down the length of the bore. A narrow vent, drilled through the breech into the bore, allowed access to the main powder charge after it was loaded, so that it could be ignited from the outside of the barrel via a priming charge inserted into the vent. To modern eyes, this transition—from breech-loading, a common feature of nearly all modern firearms, to muzzle-loading, which seems quaint and old-fashioned—appears retrograde. But it was actually a great leap forward. A cast, muzzle-loading cannon does not leak gas at the breech. The inherent strength of its construction meant that it could tolerate heavier charges, heavier projectiles, and more powerful powders without bursting.

That added strength came in handy, for gunpowder too was evolving. The constituent elements and their proportions would remain essentially the same for a long time, but the method of processing the ingredients was becoming more sophisticated. The original formulation of gunpowder, popularly known as serpentine, was compounded dry, the ingredients ground together to make a fine dust. When jostled in transport, the charcoal, saltpeter, and sulfur tended to separate, so the gunpowder would have to be reblended before use. That was a tricky and hazardous chore, one best left to an experienced gunner.

At the end of the Middle Ages, though, European powder makers had stumbled upon the process of corning. Corned powder was made by moistening the mixed serpentine, usually with water, sometimes with other liquids; artisans passionately debated the relative virtues of wine and urine for corning. The dampened powder was pressed into cakes, allowed to dry thoroughly, and then milled into “grains” or “corns.” Corned powder didn’t separate, didn’t have to be reblended before use, and gunners found that it burned more efficiently and predictably than serpentine. Soon powder makers were producing specialty powders: slower-burning, coarse-grained powder for artillery, finer powders for small arms, the finest powder for priming. Gunners discovered, too, that the corned powder was more powerful, and for that cast guns were perfectly suited. Hoop-and-stave guns were nowhere near sufficiently robust to handle the new formulations, and they began to fade away.

Cannon tubes cannot stand on their own. They require a carriage or mount, for transportation and for aiming. The earliest mounts were simple wooden beds to which the gun tube could be strapped. Wheeled gun carriages, which first appeared in Europe early in the 16th century, were far more mobile, and made the process of aiming simpler and more precise. When combined with a new design feature called the trunnion—a pair of solid metal cylinders projecting from the sides of the cannon barrel just forward of the tube’s center of gravity, cast integral with the barrel—the wheeled carriage was nothing short of revolutionary. Trunnions held the gun more securely to the carriage, and—most important—they made it so the gun could be elevated or depressed, tilting the muzzle up or down so as to increase (or decrease) the gun’s range. Ultimately, the wheeled carriage would make possible the first truly mobile field artillery, cannon that could be used on the battlefield alongside infantry and cavalry, and deployed as necessary. That day, though, was still some ways off. For now, cannon were too bulky to play an important role outside of the siege.

Artillery ammunition was simple. The most common form at the time of the Renaissance was the solid shot, a simple sphere, which in the early days of gunpowder artillery was usually made of chipped stone. Stone balls had a few advantages over cast-iron: they could be produced on-site during a siege, for instance, and they were typically lighter than cast-iron balls of the same size. Cast-iron shot, on the other hand, tended to hit harder and travel farther than stone, but their greater weight required a heavier powder charge and therefore were more stressful on gun barrels. But once cast-metal guns became available, the cast-iron solid shot caught on.

What made iron shot practical was an innovative and novel concept: standardization. Here, history has given the lion’s share of the credit to a remarkable team of brothers, Jean and Gaspard Bureau. The Bureau brothers were not soldiers so much as they were professional artillerists, and until the 18th century European artillerists considered themselves members of an elite, highly technical craft guild rather than military men. The Bureau brothers, as manufacturers and professional gunners, understood cannon inside and out. During the last two decades of the Hundred Years’ War, they served as commanders of the French artillery train.

Their king, Charles VII (r. 1422–1461) of France, trusted the Bureau brothers and allowed them much latitude, and the brothers put that trust to good use. They encouraged gun-founders to use cast iron instead of the more expensive cast bronze, and they promoted cast-iron shot over stone. By far their greatest achievement was the reduction in the number of types of cannon to a few standard models. In the 15th century, long before manufacturing introduced the notions of interchangeable parts and precision measurement, standardization was a pretty loose concept. Cannon were still individually crafted, as everything was.

Rather than leave the dimensions of cannon tubes up to the gun-founders, as had been the practice before, the Bureaus set rough universal measurements to which all makers had to adhere. Guns of a particular class would all be roughly the same length and the same weight, of the same materials, and use the same carriage. More important, they would all have the same bore diameter, which meant that they could all fire the same shot.

Excerpted, with permission, from Firepower: How Weapons Shaped Warfare, by Paul Lockhart. Copyright © 2021 by Paul D. Lockhart. Published by Hachette Book Group Inc.