Robert Lucas was a model of humility in the field of economics.

Robert Lucas Jr., an economist who had won the Nobel Prize, died a little more than two weeks ago. This news made the loss of intellectual fellow-traveler Edward Prescott, who died in December, even worse.

I have said in other pieces that there shouldn't be a Nobel Prize in economics. I still think this is true. But I can see that, since there is a Nobel Prize in economics, the people who win it are important indicators of how the field thinks.

Robert Lucas was a smart economist who set a good example for the field. He did a lot of things, but the Lucas Critique is probably his most well-known work.

There are many problems with Keynesian economics, but the most interesting idea is that Keynesian economists came to believe that inflation and unemployment are two sides of the same coin. In other words, unemployment goes down when inflation goes up and vice versa.

The Phillips curve is what economists call this obvious trade-off. One important thing to remember is that John Maynard Keynes did not come up with the idea of the Phillips curve. However, his intellectual heirs at the time thought it was a reasonable extension of his basic framework for macroeconomics. Alan Blinder, an economist, put it this way.

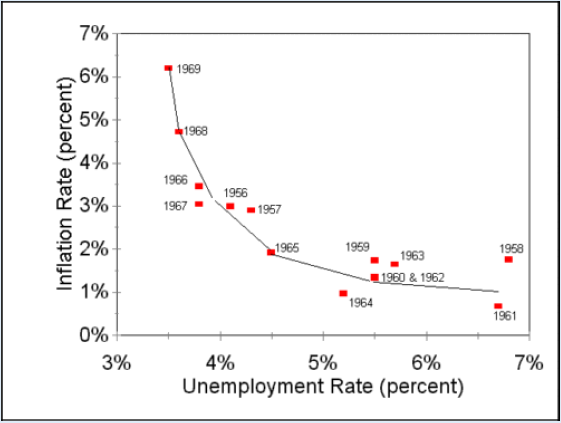

So, what did happen? At first, things did work. Look at this picture to see how unemployment and inflation compare.

Before we can figure out what happened, we need to know how the Phillips curve was meant to work. Basically, when inflation started to rise and prices went up, job ads would look like they were offering better wages.

If everything costs 10 times more, including labor, a job that used to pay $3 an hour would become a $30 an hour job all of a sudden. Well, to people who aren't used to higher prices yet, a job that pays $3 an hour might sound bad, but a job that pays $30 an hour might sound a lot better. In other words, better nominal wages made people take jobs they wouldn't have otherwise.

The idea behind using the Phillips curve in policy is that policymakers can trick regular people into doing what they want them to do.

Keynesian strategy at the time was based on the idea that in the long run, experts would know more than regular people. Lucas turned this idea upside down. Why not assume that smart and creative people will be able to understand the basics of macroeconomic models and change their beliefs based on what they know?

In other words, people started to learn in the 1970s that the jobs they had taken were not as well-paid as they had thought. By making prices go up, inflation "tricked" them into taking the jobs. But no more. People knew that 6% inflation meant that their real wages were 6% lower.

Inflation would have to go up even more than people thought it would in order for unemployment to go down again. Because of this, the Phillips curve goes to the right in the 1970s. For people to be fooled, inflation rates had to keep going up. By 1980, not even a rate of inflation of almost 13% could fool people. At 7%, unemployment stayed high and steady.

The Keynesian way of thought at the time was that policymakers were experts outside of the economic model and could change parts of the model, like the inflation rate, to change other models, like unemployment.

But as the Lucas review shows, people are not just chess pieces that move in response to the changes that experts make to the rules. People are smart and attentive instead. You can't always expect people to act the same way when things change.

In the social sciences, the topics (people) think and act differently than in the natural sciences. They can learn how policymakers work and beat them at their own game.

The Lucas Critique is not just about where the Phillips curve was in time. The Lucas critique questions any macroeconomic model that believes people won't change when policies are put into place.

Robert Lucas's standard makes analysts think that people in the economy are smart and responsive. Any strategy that assumes that people are consistently stupid can and should be questioned.

Robert Lucas was a shining example of how to be humble in his field. His work pushes economists to talk about creative, ambitious people again when they talk about the economy as a whole. So, even though I don't like the Nobel Prize in economics, I can say without a doubt that Robert Lucas earned his. Rest in peace.

I have said in other pieces that there shouldn't be a Nobel Prize in economics. I still think this is true. But I can see that, since there is a Nobel Prize in economics, the people who win it are important indicators of how the field thinks.

Robert Lucas was a smart economist who set a good example for the field. He did a lot of things, but the Lucas Critique is probably his most well-known work.

The Economic ‘Experts’

To understand how important the Lucas critique is, it helps to go back to the 1960s for a bit. In the 1960s, the Keynesian model was the way most people thought about the economy as a whole (macroeconomics).There are many problems with Keynesian economics, but the most interesting idea is that Keynesian economists came to believe that inflation and unemployment are two sides of the same coin. In other words, unemployment goes down when inflation goes up and vice versa.

The Phillips curve is what economists call this obvious trade-off. One important thing to remember is that John Maynard Keynes did not come up with the idea of the Phillips curve. However, his intellectual heirs at the time thought it was a reasonable extension of his basic framework for macroeconomics. Alan Blinder, an economist, put it this way.

When the 1960s came along, Keynesians were able to put their ideas to the test. Between 1958 and 1962, unemployment ranged from 5.5% to 7%. In other words, there were many people out of work. The Keynesians' answer was to use a monetary strategy that caused inflation to rise. The Phillips curve shows that when you print more money, people spend more, which leads to more jobs.“Prior to 1970, Keynesians believed that the long-run level of unemployment depended on government policy, and that the government could achieve a low unemployment rate by accepting a high but steady rate of inflation.”

So, what did happen? At first, things did work. Look at this picture to see how unemployment and inflation compare.

Figure 1—Inflation and Unemployment in the 1960s

As you can see, as inflation increased the unemployment rate fell. This is exactly what Keynesians predicted with the Phillips curve. But there was a problem. This didn’t last forever. Look what happened in the 1970s.

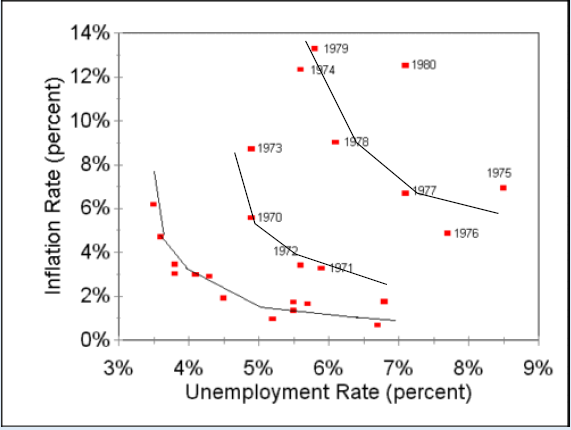

Figure 2—Inflation and Unemployment in the 1970s

Both inflation and unemployment had gone up by 1980. In other words, there was no longer anything to be gained or lost. The Keynesian rules for big-picture economics fell apart right in front of everyone's eyes. There was something wrong with "expert" thought.Before we can figure out what happened, we need to know how the Phillips curve was meant to work. Basically, when inflation started to rise and prices went up, job ads would look like they were offering better wages.

If everything costs 10 times more, including labor, a job that used to pay $3 an hour would become a $30 an hour job all of a sudden. Well, to people who aren't used to higher prices yet, a job that pays $3 an hour might sound bad, but a job that pays $30 an hour might sound a lot better. In other words, better nominal wages made people take jobs they wouldn't have otherwise.

The idea behind using the Phillips curve in policy is that policymakers can trick regular people into doing what they want them to do.

The Lucas Critique

In the 1960s and 1970s, activist policies like using the Phillips curve were a clear target of the Lucas Critique. Robert Lucas's main point was that policymakers can't assume that people will always be fooled into making the same mistake.Keynesian strategy at the time was based on the idea that in the long run, experts would know more than regular people. Lucas turned this idea upside down. Why not assume that smart and creative people will be able to understand the basics of macroeconomic models and change their beliefs based on what they know?

In other words, people started to learn in the 1970s that the jobs they had taken were not as well-paid as they had thought. By making prices go up, inflation "tricked" them into taking the jobs. But no more. People knew that 6% inflation meant that their real wages were 6% lower.

Inflation would have to go up even more than people thought it would in order for unemployment to go down again. Because of this, the Phillips curve goes to the right in the 1970s. For people to be fooled, inflation rates had to keep going up. By 1980, not even a rate of inflation of almost 13% could fool people. At 7%, unemployment stayed high and steady.

The Keynesian way of thought at the time was that policymakers were experts outside of the economic model and could change parts of the model, like the inflation rate, to change other models, like unemployment.

But as the Lucas review shows, people are not just chess pieces that move in response to the changes that experts make to the rules. People are smart and attentive instead. You can't always expect people to act the same way when things change.

In the social sciences, the topics (people) think and act differently than in the natural sciences. They can learn how policymakers work and beat them at their own game.

The Lucas Critique is not just about where the Phillips curve was in time. The Lucas critique questions any macroeconomic model that believes people won't change when policies are put into place.

Robert Lucas's standard makes analysts think that people in the economy are smart and responsive. Any strategy that assumes that people are consistently stupid can and should be questioned.

Robert Lucas was a shining example of how to be humble in his field. His work pushes economists to talk about creative, ambitious people again when they talk about the economy as a whole. So, even though I don't like the Nobel Prize in economics, I can say without a doubt that Robert Lucas earned his. Rest in peace.