More On: Central Bank

Central bankers blame the victims in order to divide and rule

It's not crazy to worry about a digital currency run by the central bank

The chances that the Fed will cause the next bust are going up

Targeting inflation and keeping prices stable have problems and haven't worked well

Without the Fed's easy money, home prices will keep going down

Central bankers follow inflation 'target' in their pursuit of 'price stability.' Not surprisingly, they usually miss their targets -- quite badly -- and we now are living one of those moments.

Most people think that Albert Einstein said, "Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and over again and expecting different results." This quote was meant to be a story about quantum insanity, but it could also be a story about how to handle inflation. Even though both the Bank of England and the Federal Reserve want to keep their target rates at 2%, the UK's inflation rate has only gone from 11.1 to 10.7%. Since inflation is still very high, it may be time to talk about the problems with policies that try to keep it low.

The UK started using inflation targeting as a monetary policy in 1992 to keep inflation at a level that could be planned for, to keep track of the inflation rate, and to keep prices stable. But there are a lot of problems with targeting inflation. It is important to know all of the problems with inflation targeting and to have a more complete definition of inflation. Most people think of inflation as a general rise in prices. However, this definition doesn't say anything about what causes inflation; it only talks about the effect.

Inflation has always been caused by a rise in the amount of money that is in circulation that is too big for the amount of goods and services that money can buy. This definition says the most accurate thing about what causes inflation, which is that an inflationary policy makes prices go up in general. Prices won't all go up at the same rate because people want different things in different amounts and at different times, and some things have less flexible demand than others.

If you use the common definition of inflation, you don't take into account that the general price level can change because of a shortage of a good that is used in more than one production period or process. As Nicolás Cachanosky, an assistant economics professor at Metropolitan State University, says, "defining inflation by describing a change in a variable that can have multiple causes invites confusion. This confusion can lead to mistakes in monetary policy in the long run. A better way to describe inflation would be to look at what causes it instead of what it does. An inflation target policy just makes sure that inflation stays positive over a long period of time. This is also called "secular inflation." Keeping in mind a definition of inflation that focuses on the cause rather than the effect and the loss of purchasing power, we can see that a policy of inflation targeting (secular inflation) leads to a shorter timeframe for the utility of money (expiration date of money).

To show how the date on money works, let's say a person has two British pounds. Let's say this person, A, saves half of every pound he earns. In this case, A will spend one pound and save one pound. With an inflation-targeting policy of 2%, the pound A saves will be worth 98 pence after a year. A must earn an extra two pence per pound next year to keep the same level of buying power and the same real value of his savings. Due to this annual inflation goal of 2%, A will have to earn an extra four pence per pound in two years if he wants his money to still be worth the same in real terms. If he doesn't, his money will only be worth 96 pence per pound.

People tend to prefer current consumption over future consumption because of how individual time preference works. This means that A is likely to change his consumption preferences to favor current consumption. This is especially true if A thinks that not spending money today means he won't be able to spend as much next year because the real value of his money has gone down. This would cause A's rate of saving to drop to 30 pence per pound and his rate of spending to rise to 70 pence per pound.

In the end, this causes the speed of money to go up and the demand to hold money to go down as more money circulates. Because of this, there is an artificially high level of consumption, people don't save money, and inflation's effects are fully felt (a general rise in prices). Many Austrian economists don't think velocity is a useful idea, but it's really just a way to measure how fast money is spent in the economy as a whole. It's hard to argue against the fact that if velocity were zero (no one spent anything), inflation would no longer cause prices to go up in general.

What about making sure prices stay the same? Is it not good to have prices that don't change? The answer has to do with the fact that inflation targeting doesn't work when there are big changes in the supply, like when productivity goes up. In fact, these kinds of price stability measures, like targeting inflation, send the wrong message about the value of business ventures and hide real productivity gains.

Most economists think that deflation is bad for the economy, so central banks try to stop it. When the price of one or two consumer goods goes down, it's not a big deal. However, when the price of all or most goods goes down, it's a sign of an economic depression.

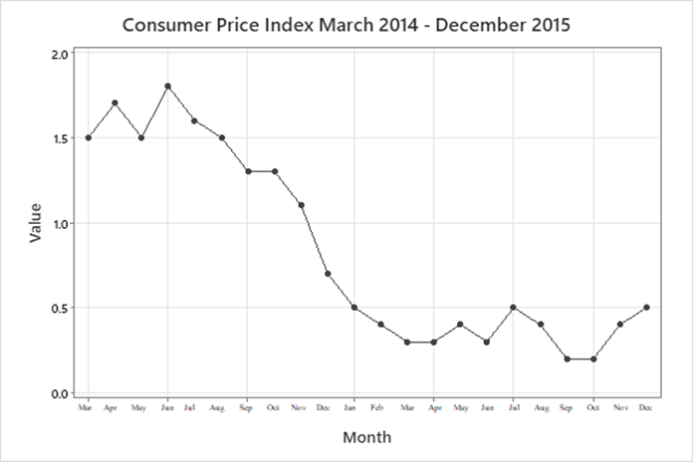

From March 2014 to December 2015, both consumer and producer prices kept going down in the UK. This is what the Bank of England would have called a twenty-two-month depression. From March 2014 to December 2015, the consumer price index (CPI) is shown below. Over a period of twenty-two months, the CPI dropped by about 67 percent.

![Ascough1]()

![Ascough2]()

![Ascough3]()

Monetary authorities shouldn't try to keep prices stable and keep inflation rates up, because this makes the economy less stable. Prices should change to show how productive each industry is, how the economy is doing, and how well (or badly) resources are being used. Instead, the people in charge of money should try to keep the amount of money in circulation stable. In the past, there was a rule like this that tried to reach monetary equilibrium and financial stability. The Peels Act of 1844 put an end to that, which was bad for the UK. Inflation is (and always will be) the future.

The UK started using inflation targeting as a monetary policy in 1992 to keep inflation at a level that could be planned for, to keep track of the inflation rate, and to keep prices stable. But there are a lot of problems with targeting inflation. It is important to know all of the problems with inflation targeting and to have a more complete definition of inflation. Most people think of inflation as a general rise in prices. However, this definition doesn't say anything about what causes inflation; it only talks about the effect.

Inflation has always been caused by a rise in the amount of money that is in circulation that is too big for the amount of goods and services that money can buy. This definition says the most accurate thing about what causes inflation, which is that an inflationary policy makes prices go up in general. Prices won't all go up at the same rate because people want different things in different amounts and at different times, and some things have less flexible demand than others.

If you use the common definition of inflation, you don't take into account that the general price level can change because of a shortage of a good that is used in more than one production period or process. As Nicolás Cachanosky, an assistant economics professor at Metropolitan State University, says, "defining inflation by describing a change in a variable that can have multiple causes invites confusion. This confusion can lead to mistakes in monetary policy in the long run. A better way to describe inflation would be to look at what causes it instead of what it does. An inflation target policy just makes sure that inflation stays positive over a long period of time. This is also called "secular inflation." Keeping in mind a definition of inflation that focuses on the cause rather than the effect and the loss of purchasing power, we can see that a policy of inflation targeting (secular inflation) leads to a shorter timeframe for the utility of money (expiration date of money).

To show how the date on money works, let's say a person has two British pounds. Let's say this person, A, saves half of every pound he earns. In this case, A will spend one pound and save one pound. With an inflation-targeting policy of 2%, the pound A saves will be worth 98 pence after a year. A must earn an extra two pence per pound next year to keep the same level of buying power and the same real value of his savings. Due to this annual inflation goal of 2%, A will have to earn an extra four pence per pound in two years if he wants his money to still be worth the same in real terms. If he doesn't, his money will only be worth 96 pence per pound.

People tend to prefer current consumption over future consumption because of how individual time preference works. This means that A is likely to change his consumption preferences to favor current consumption. This is especially true if A thinks that not spending money today means he won't be able to spend as much next year because the real value of his money has gone down. This would cause A's rate of saving to drop to 30 pence per pound and his rate of spending to rise to 70 pence per pound.

In the end, this causes the speed of money to go up and the demand to hold money to go down as more money circulates. Because of this, there is an artificially high level of consumption, people don't save money, and inflation's effects are fully felt (a general rise in prices). Many Austrian economists don't think velocity is a useful idea, but it's really just a way to measure how fast money is spent in the economy as a whole. It's hard to argue against the fact that if velocity were zero (no one spent anything), inflation would no longer cause prices to go up in general.

What about making sure prices stay the same? Is it not good to have prices that don't change? The answer has to do with the fact that inflation targeting doesn't work when there are big changes in the supply, like when productivity goes up. In fact, these kinds of price stability measures, like targeting inflation, send the wrong message about the value of business ventures and hide real productivity gains.

Most economists think that deflation is bad for the economy, so central banks try to stop it. When the price of one or two consumer goods goes down, it's not a big deal. However, when the price of all or most goods goes down, it's a sign of an economic depression.

From March 2014 to December 2015, both consumer and producer prices kept going down in the UK. This is what the Bank of England would have called a twenty-two-month depression. From March 2014 to December 2015, the consumer price index (CPI) is shown below. Over a period of twenty-two months, the CPI dropped by about 67 percent.

Source: Data from OECD Data (Inflation [CPI], accessed December 22, 2022).

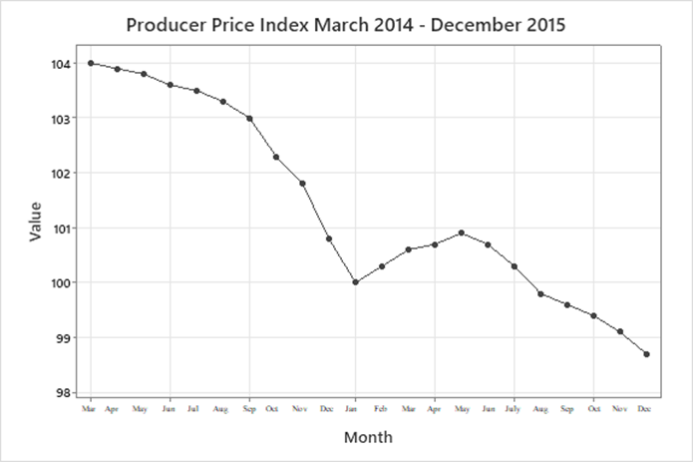

Over the same twenty-two-month period, the producer price index (PPI) fell by 5 percent.

Source: Data from OECD Data (Producer Price Indices [PPI], accessed December 21, 2022).

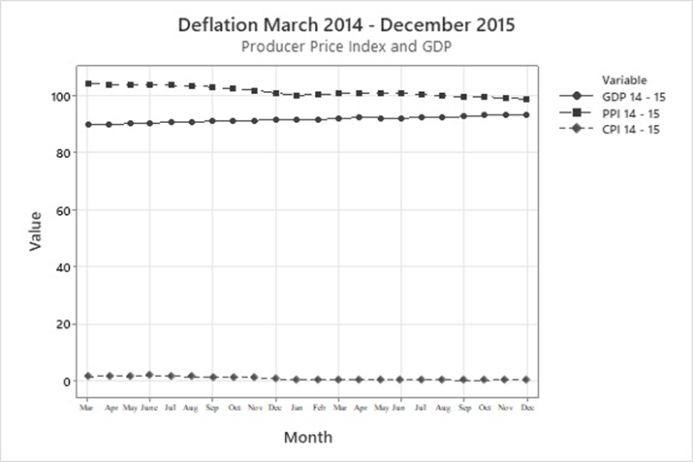

However, looking at gross domestic product’s (GDP) monthly changes over the same twenty-two-month period, the economy was not depressed. In fact, GDP gradually increased.

Source: D. Clark, “Monthly Index of Gross Domestic Product in the United Kingdom from January 1997 to October 2022f” (data set), December 12, 2022, Statista.

The dotted lines show how CPI, PPI, and GDP change over time. The CPI and PPI are both going down slowly, but instead of GDP going down, the economy grew. Targeting inflation and making sure prices stay stable hide real changes in productivity. By trying to keep nominal prices stable, real changes in productivity, whether they are good or bad, are either slowed down or completely hidden.Monetary authorities shouldn't try to keep prices stable and keep inflation rates up, because this makes the economy less stable. Prices should change to show how productive each industry is, how the economy is doing, and how well (or badly) resources are being used. Instead, the people in charge of money should try to keep the amount of money in circulation stable. In the past, there was a rule like this that tried to reach monetary equilibrium and financial stability. The Peels Act of 1844 put an end to that, which was bad for the UK. Inflation is (and always will be) the future.