More On: cryptocurrency

It looks like Tom Brady lost a huge amount of money in the FTX Crash

Why the FTX bubble burst and how it hurt people

Why Sam Bankman-Fried's world fell apart

The cryptocurrency exchange Bitfront closes

FTX put your cryptocurrency in a 'crypt,' not a 'vault.'

The arrogance and lack of skill of business giants is an old story. But the risk has grown because digital technology is so easy to scale up.

When the inevitable biopic about Sam Bankman-Fried and the collapse of his FTX cryptocurrency exchange comes out, it will be interesting to see if even skilled filmmakers can make Bankman-Fried seem like a compelling villain. The 30-year-old founder of FTX has said that he made a lot of mistakes. But even though the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Justice Department are now looking into his business, there is no proof that he has done anything wrong. His sins seem more like those of a young, careless person who got in over his head and didn't realize that running a $32 billion company in a volatile financial sector is a full-time job.

Bankman-Fried became a lobbyist for FTX and the crypto industry as a whole. He got involved in a wide range of ambitious philanthropic projects, spent a lot of time tweeting and giving interviews, and, most importantly, kept building up his original trading firm, Alameda Research, at the same time as FTX. In the end, it looks like the Alameda anchor was what brought down the FTX ship.

CoinDesk spoke to several current and former @FTX_Official and Alameda employees who agreed to talk on the condition of anonymity.

— CoinDesk (@CoinDesk) November 12, 2022

“The whole operation was run by a gang of kids in the Bahamas,” a person familiar with the matter said.https://t.co/nO5n2bOuc7

David Yaffe-Bellany of the New York Times did an investigation based on interviews with Bankman-subordinates Fried's and close friends. He found that the business operations of FTX and Alameda were often mixed together. Caroline Ellison, a former trader and one-time lover of Bankman-Fried, has been in charge of Alameda for the past few years. And, Yaffe-Bellany says, "a guest who visited FTX's complex in the past few months said that Ms. Ellison had been sitting near computers that were showing [FTX's] trading data." By design, Bankman-operations Fried's blurred the lines between work and personal life. For example, all of the FTX senior brain trust lived, worked, and often dated in the same isolated Bahamas resort compound.

Techno-futurists who see the dot-com billionaire class as a way out of the snobbish, bureaucratized business culture may find this kind of work environment ideal. The movie version of Bankman-Odyssey Fried's will have beautiful sets, if nothing else. Here was a group of young, tech-savvy globetrotters working in T-shirts and cargo shorts to build the financial infrastructure of the future. National laws and borders didn't matter much to these crypto kings. When Bankman-Fried found US regulations too restrictive, he moved to Hong Kong, but then he decided he liked the West Indies better.

And since crypto is a completely virtual asset whose value is backed by nothing but a complicated set of cryptographic algorithms, Bankman-Fried didn't have to worry about a supply chain, deal with labor unions, or keep stock in warehouses. Between FTX and Alameda, Bankman-Fried and his sometimes girlfriend never had more than about 350 employees working for them. This is about the same number of people who work at a single Walmart Supercenter. In other words, it was the top job in the laptop class.

This highly mobile and geographically dispersed business model is typical of the crypto industry as a whole. The pioneers of the crypto industry are very skeptical of not only the traditional banking system but also the checks and balances, oversight mechanisms, and reporting requirements that govern how it works. Putting aside the question of whether or not it is possible (or even desirable) to challenge (much less overthrow) the dominance of fiat currencies, FTX's story shows that even the most mundane legal, regulatory, and human resources rules can be helpful. It's one thing to make a set of currencies based on a libertarian philosophy, but it's a different thing to make corporations based on that same philosophy. An algorithm can be perfected, or at the very least, it can be set up so that it corrects itself automatically. But not so with a person.

In the case of FTX, having someone in the Bahamas who was ready and able to blow the whistle on suspicious related-party transactions, like the ones Bankman-Fried is said to have used to bail out Alameda with FTX assets, would have been a good thing. Bankman-Fried put a lot of faith in his own judgment (it's said that he doesn't even read books), and he mostly stuck to a small group of loyal subordinates whose lavish lifestyles were made possible by his patronage. No one in that group was able to convince him, which wasn't a surprise, that his empire was becoming financially unstable.

The arrogance and lack of skill of business leaders is not a new story, of course. But the risk has grown because digital technology is so easy to scale up. In the industrial age, an entrepreneur with a groundbreaking idea, like a new way to make plastic injection molds or a new drug, would usually have to spend years in a lab, build pilot projects, apply for patents, spread the word at trade shows, find skilled engineers, and find distributors before making a single sale. Even with the help of computers, it still takes an established car company about four years to get a car from the idea stage to the showroom. But an algorithm for taking advantage of inefficiencies in the crypto markets, like the one Bankman-Fried started using in 2018 at the age of 26, can go from being talked about in a Reddit thread to being used in a way that makes money in a matter of hours. The careers of industrial age moguls often followed the natural working lives of their most important capital assets, like blast furnaces, kilns, railroads, and car factories. This is why so many of these people were still important well into their old age. In the digital age, on the other hand, magnates can go through whole boom and bust cycles while still in their 20s.

Also, the traditional way to build up an industrial operation has been for entrepreneurs to work with bankers, investors, lawyers, and auditors. All of these people tend to be conservative, so they tend to make operations more cautious. Capital costs and other barriers to entering a market are often so high that entrepreneurs sell out to established operators or at least fill their boards of directors with people from outside the company. But because crypto and other digital businesses can be scaled instantly and globally with little capital, entrepreneurs can avoid all of these influences. This lets them live like old teenagers from an Adam Sandler movie, often in small peer groups made up of similarly naive brainiacs.

Network effects are another part of digital culture that can make it easier for plutocrats to act on impulse. Even though Elon Musk is not a teenager, he can act like one on Twitter because he knows that millions of users are stuck with his product because of our carefully built network of friends, contacts, and business partners: The collective-action problem will make it hard for a lot of people to switch to a different product, like Mastodon. This helps explain why so many business journalists are still obsessed with Musk's behavior at Twitter, despite the fact that the company doesn't have much of an economic impact. The bitter tone of their reporting shows that they don't like how much power Musk has over our professional subculture, and they feel bad that we give him more power with every tweet we send, even ones that criticize Twitter.

Imagine that Musk's business path had been different—that he had bought Tesla with the tens of billions of dollars he made from starting Twitter instead of the other way around. Would Musk be brave enough to fire half of Tesla's engineers in his first month on the job? Or show that he doesn't care about a lot of Tesla's customers? Nothing like this would ever happen because cars are mostly interchangeable and switching brands is easy. And if Tesla had a disaster, people would just switch to other brands.

There is no easy way to solve any of these problems, except for the way people act. Power users who only use Musk's service to connect with the rest of the world and can't even imagine a world without Twitter are the most dependent on Twitter's network effects. In reality, Facebook, LinkedIn, Substack, TikTok, Instagram, YouTube, and a dozen other services can be used in ways that are similar to Twitter's best features—sharing content, promoting yourself professionally, and connecting with people—but with fewer of Twitter's negative side effects (shaming, mobbing, and ideological self-segregation).

None of these other social media sites can fully replace Twitter on their own. But on the other hand, one thing we can learn from this Musk moment is that we shouldn't use social media as a one-stop shop: Even if Musk sold Twitter tomorrow, there's no guarantee that the next owner would be less rash and unpredictable. In the long run, the only way for users to avoid being held hostage by fickle digital overlords is to start treating social media services like any other consumer good (or professional tool) that exists in a competitive marketplace. This means that we should use social media services more or less (or not at all) depending on how their costs and benefits compare to those of competing services.

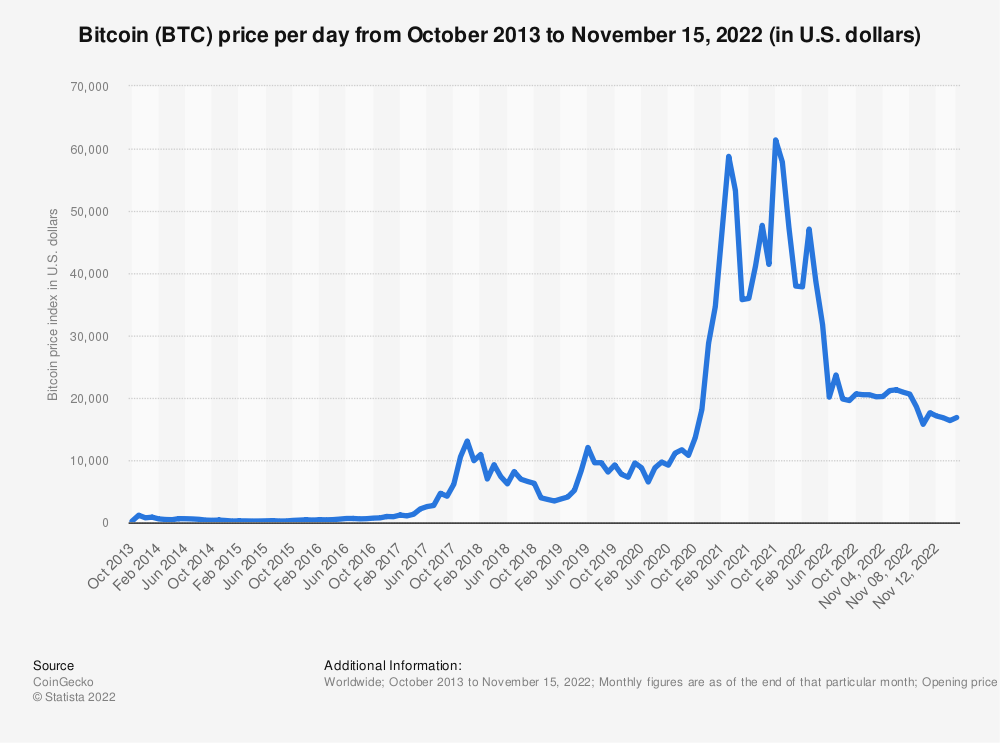

When it comes to FTX and crypto in general, consumers need to learn something even simpler. In fact, it reminds us of one of the first things high school students learn in their first economics classes: that money has more than one use, such as being a medium of exchange and a place to store value. Many crypto fans seem to think that because crypto has shown itself to be a really innovative way to trade, it must also be a good way to store value, even though this is not the case. But it's not, as any Bitcoin investor from the year 2021 can tell you. A good rule of thumb is that you should think twice before investing in anything that has no real value and whose price goes up and down based on Twitter feuds between billionaires and the daily chatter of fanatical crypto bros on Discord.

Find more statistics at Statista

There have been many asset bubbles and market manias in the past. And people who lost their FTX assets or were hurt by the "crypto winter" in general have been in good company in the past. There's nothing wrong with it. In fact, it's important to remember that some of the same media outlets that now portray crypto as a Ponzi scheme and Bankman-Fried as a likely fraud were, just a few months ago, building up his reputation as a boy wonder and even a possible industry savior.

The lesson here is not that all crypto users are fools, let alone that "You Can Forget About Crypto Now," as one provocative Atlantic headline put it. It's that even those of us who still use crypto for some types of financial transactions shouldn't put our life savings in it. If the Bankman-Fried biopic, which is sure to be coming to a theater near you soon, can find a way to get that message across, it will be a very good movie.

** Information on these pages contains forward-looking statements that involve risks and uncertainties. Markets and instruments profiled on this page are for informational purposes only and should not in any way come across as a recommendation to buy or sell in these assets. You should do your own thorough research before making any investment decisions. All risks, losses and costs associated with investing, including total loss of principal, are your responsibility. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of USA GAG nor its advertisers. The author will not be held responsible for information that is found at the end of links posted on this page.