'Every time we hit each other in practice, this nagging feeling that she had an unfair advantage would arise. 'It was like slamming into a brick wall for me.'

In eighth grade, I made the decision to participate in American football—the sort with helmets and touchdowns—as a sport. It was 1994, and the town's lone football team for boys was still in existence at the time. It was despite this that my parents signed me up without hesitation, believing that my involvement would be acceptable. As it turned out, the league's administrators disagreed.

The league's president asked that I demonstrate my ability to compete. We were both karate students, and he made me compete against the sensei's son in a sham strength test. Since prepubescent girls and boys are generally physically equal, this was an unusual trial. We're far from having a David-versus-Goliath showdown here, to put it mildly. Even though we were politely obliged, my mom says we were all irritated by the situation. My recollection of the event is hazy, but it appears that I was victorious. According to my mother, I "nailed" my opponent in a convincing manner during the competition.

For the next four years, I was a member of the team. I was a star running back for the first two years of my career. However, by the time I was in seventh grade, I had begun to fall behind the boys, who were suddenly getting bigger. At 13, it became apparent that, at 5'10" and 120 pounds, I was no longer able to compete with the much larger and more muscular boys. I said my goodbyes, appreciative for the experience and delighted to have been one of the league's first two female players.

I didn't play football again for almost ten years. In 2006, I was 20 years old when I joined a football league for women only. But I fell right back into the happiness I felt as a child. I played on and off for a few different teams in the area. And yes, skeptics, this was real football with pads, hitting, tackling, and everything else.

By 2016, I had moved up to a top team. Some of our coaches had been in the NFL, but there was a lot of competition for spots on the team, and veterans didn't get much special treatment. Some of the best players would fly in from out of state, sometimes just for a few practices, and then start the game. This was not a league where everyone got a chance to play and the whole point was to have fun. Those who were good got to play. If no, then no.

By this point in my career, injuries had already slowed me down a bit. But as recently as the 2015 season, I was still playing enough to stay committed to the team. The next year, though, things changed when a trans woman joined our team.

Jamie, which is what I'll call her, played the same spot on defense as I did. She was young, she had a great sense of humor, and she could really beat people up. Seeing it was pretty exciting. She went to every practice, did her best, and was a good teammate in general. We were friends, and I would often drive her to practices while we talked about work. I've never had anything against her, and I still don't. The team league let her play. And she was just doing what the rest of us were doing: playing a sport we all loved. I also didn't want to think about the fact that Jamie was much better than her female teammates and opponents at the time. And if someone had asked me about it, I would have defended her right to play in the league.

I'm not sure what my reasoning would have been, since these issues weren't as hotly debated in 2016 as they are now. But I think I thought that if a biological male over the age of puberty took the right amount of drugs, he could really be like a biological female. Maybe my interest in social justice made me want to try to see the world through Jamie's eyes, even though it cost me the chance to play in an all-league women's because she was there.

Or maybe they didn't say anything because they were afraid of being called racists. And if you're not going to say something, it's best to train yourself not to think it in the first place. (In the Big-Five personality model, biological females always score higher than males on how agreeable they are. But that's a sidetrack for a different day.)

Again, this was before high-profile debates about trans women started popping up all over sports, from a Connecticut high school track team to swimmer Lia Thomas to Olympic weightlifter Laurel Hubbard to cyclist Rachel McKinnon to MMA fighters Alana McLaughlin and Fallon Fox. I didn't think it would be that important. What could a trans woman here or there really do to hurt anyone?

But it was clear what happened. Jamie looked like a man who was built to be athletic. Even though she didn't work out or eat well, she was bigger, faster, and stronger than the rest of us. (We joked about this on the way to practice, so I know it's true.) Even though she wasn't very good at tackling, it didn't matter. If you have more strength than your opponent, it doesn't matter how bad your technique is. Most of the time, a woman her size would play on either the offensive or defensive line. But she was fast enough to play linebacker, a position usually filled by people who are strong, fast, and have muscles that aren't as spread out. She towered over most of the other linebackers, and she could catch most running backs and quarterbacks even if she had started out in the wrong place. Even though the rest of us tried to learn the plays and formations by heart, she didn't really need to: She could get anywhere on the field because she was fast and strong, even if it meant going through other players.

Every time we hit each other in practice, I couldn't shake the feeling that she was better than us. I felt like I had hit a brick wall, which was a deflating experience. Even the strongest women I've met didn't seem as strong as they were. I was too small to play football with boys in high school and college, and I was okay with that. But those were not leagues for women. I was an adult, finally getting the chance to compete with other women, and I was being outmuscled by someone who, from what I could tell, would be an average or below-average player on a men's team. I felt like I was 12 again and couldn't keep up with the boys.

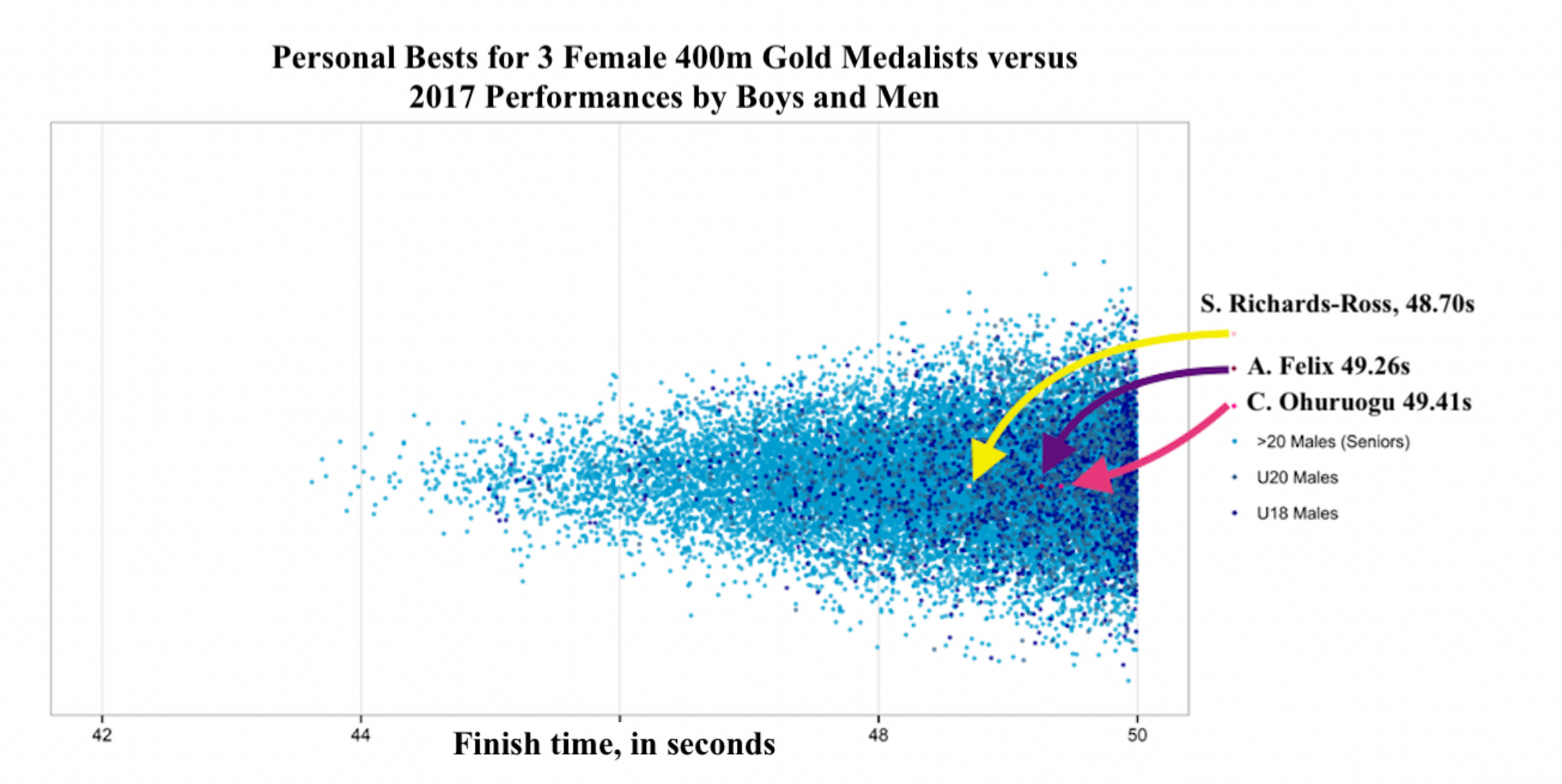

Looking back, it's painfully clear how unfair it was for a girl to have to compete against someone who went through male puberty. Now, the research in this area can't be argued with. Even after a year of hormone therapy, one study found that trans women have a mean running speed that is nine percent faster than women. Men can punch harder, use more oxygen, and get hurt less often in sports. In a recent summary, the New York Times said, "Men, on average, have wider shoulders, bigger hands, longer torsos, and more lung and heart capacity." Muscles are denser." All of this directly leads to better sports performance. And getting less testosterone later in life can't take away all of these benefits.

Lia Thomas on the podium as a National Champion at Women's Swimming NCAAs will most likely become one of the most famous images in the history of collegiate swimming. pic.twitter.com/OXtjRt0mu4

— Kyle Sockwell (@kylesockwell) March 18, 2022

Save Women's Sports is a group that fights for female-only sports categories. They have a list of about 80 trans-identified men who have competed in a women's sports category that is available to the public. This is not a complete list of all known trans women who play sports for women. But you should still look at the catalog because the examples tend to show a common pattern: an average or below-average male athlete switches to the women's division and then breaks records in that division.

Some people who think trans women should be allowed to play female sports say that if trans women and natural females were really so different, trans women would win every competition every time. But since there aren't many trans women who play most sports, this argument can be thrown out as a straw man.

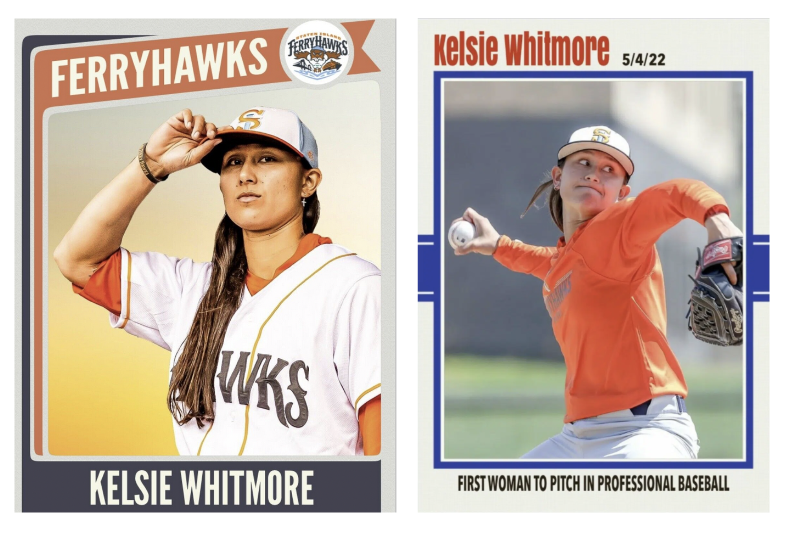

Even though some of the results of the worst male athletes and the best female athletes are the same, this isn't a good reason to let trans women play female sports. Think about how, in track and field events, even the best high school boys often do better than record-setting female Olympians. On June 12, the sports section of the New York Times led with an inspiring story about a pitcher named Kelsie Whitmore, who is one of the best women to ever play baseball. The author didn't mention until the end of the piece that Whitmore's fastball can't go faster than 80 miles per hour, which is at least 15 miles per hour slower than the average male minor league pitcher. Imagine any NFL, NBA, NHL, or MLB football, basketball, or baseball player coming out as female and then asking to play in a women's league. This is what it would be like for women's sports if a large number of elite natal males played in the women's division.

Transgender people face problems in their daily lives that the rest of us don't have to deal with, such as transphobia. People sometimes say on social media, in particular, that we should all make allowances for them to help make up for the pain and exclusion they go through. This kind of argument is also sometimes made in a legal setting. "Discriminatory things happen every day to transgender people," said Nicholas May, a lawyer who helped a trans woman in Minnesota get on a female football team. "Even these small things can cause big problems for transgender people's mental health and self-worth."

From this point of view, female athletes should "take one for the team" (i.e., the social justice team) and make accommodations for biological males who identify as female so that they can be their "true selves" and do well. As was mentioned above, this was pretty much how I thought until a few years ago, before I hit that brick wall at practice.

Until recently, what I'm saying here was thought to be taboo (at least in polite society). These claims about biology were criticized as going against the idea that transgender rights "aren't up for debate."

But absolute slogans are losing their power, in part because of the backlash Thomas's swim at the NCAA swimming finals in March caused. The recent decision by the Fédération Internationale de Natation (FINA), the world governing body for swimming, that biological males who call themselves trans women (like Thomas) won't be allowed to compete in elite women's swim races if they've already gone through any part of male puberty is a sign of the times. In 2020, the same decision was made by the global body in charge of rugby union. And it looks like track and field is going in the same direction.

None of these things are more of a sign of real transphobia than my own views. I think transgender people should have rights. But I also think that, just like in many other areas of law and policy, there are trade-offs to be made between the rights that different groups claim to have. As a child, I learned this the hard way: The boys had their own football team, but the girls didn't because there weren't enough girls who wanted to play for there to be a league for them. There are only so many resources in a town, so the people in charge have to make hard decisions. It's too bad, but I had to deal with it. Because I'm a girl who likes things that are usually done by men, I'm in the minority, which sometimes meant I couldn't do things I liked.

If I hadn't accepted that fact and instead found a way to play high school boys, I could have hurt myself seriously because I am small, even for a woman. On the other hand, trans women who want to play female contact sports put everyone else at risk of getting hurt, not just themselves. Fox, for example, is known for breaking the skull of Tamikka Brents during an MMA fight in 2014. And transgender Australian rules football player Hannah Mouncey, who is 6'3" tall and weighs 220 pounds, got into a fight on the field that broke the leg of an opponent.

These trans women are permitted to compete in male athletic divisions, even while they continue to declare their female identification, because professional male sports do not often prohibit women. However, this would necessitate a far higher level of competition. And when it comes to these disparities, it is apparently assumed that biological women, not males, will make the required adjustments.

Obviously, this is consistent with a pattern that has persisted throughout human history. It is hardly shocking that modern female athletes are expected to make sacrifices for others. Rather, it is that we are expected to pretend that doing so is a demonstration of social fairness.