More On: Pearl Harbor

The Day of Deceit: The Truth About FDR and Pearl Harbor is a book that tells the truth about FDR and Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is often misremembered

The technically clever but strategically insane attack on Pearl Harbor enraged a once-sophisticated Japanese empire, which mistakenly attacked the United States at a time of peace.

Most Americans used to agree on what happened on December 7, 1941, which was 80 years ago this year. However, given either the neglect of America's past in schools or awakened revisionism at conflict with the facts, this is no longer the case.

The Pacific War that followed Pearl Harbor was neither the consequence of America provoking the Japanese, nor was it about beginning a race war. It was about an arrogant and brutal Japanese empire mistakenly believing that its larger American opponent would not or could not halt its transoceanic aspirations.

While at peace and without a declaration of war, the Japanese Imperial Navy launched a militarily successful but strategically inept surprise attack on the US 7th Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on a Sunday morning. The attack, which was timed to coincide with subsequent bombing and invasions of the Philippines, British-controlled Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong, as well as some Pacific Islands, ensured not only an existential Pacific theater war between Japan and America, but also an existential Pacific theater war between Japan and the United States. It also precipitated the United States' participation into World War II's European theater on December 11, when both Italy and Nazi Germany declared war on America. If the latter had not done so, it is possible that the United States would have focused only on Japan and gotten Japan out of the war much sooner.

Revisionists frequently reference conspiracy theories that the Roosevelt administration enticed Japan into the war by restricting oil supplies to Tokyo (only five months before Pearl Harbor) or by recklessly relocating the 7th Fleet from San Diego to an intentionally exposed and poorly defended Pearl Harbor.

Such opposing viewpoints are unpersuasive since the one-sided source of tensions has been obvious to everybody for more than a decade. In 1931, Japan invaded Manchuria. In 1937, it invaded China's mainland, resuming the conflict. It annexed French colonial Indochina in September 1940. By 1940, the concept of a Japanese Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere was circulating unofficially as a model for combining Japan's projected imperial wartime acquisitions of China and former British, American, French, and Dutch colonial holdings.

The mercantile system was envisioned as an Asian version of a would-be Napoleonic Europe, based on Japan's alleged racial superiority and the propagandistic and cynical notion that even harsher Japanese imperialism would be less resented by Asians in the Pacific than current Western nation-building colonialism. Given the Japanese mass civilian executions of captured Asians at Nanking, China, and the massacres that followed the takeover of Singapore, such crass propaganda was never taken seriously outside of Tokyo.

Loss of Deterrence

For most of the 1930s, Western nations had appeased and gave the Japanese war machine everything it needed. If racism played a role in the rising tensions, it was primarily the Japanese belief that their prosperous, industrialized nation was a natural reflection of their inherent racial superiority. If Japan overstated its might chauvinistically, the allies countered by downplaying the Japanese danger based on their own racialist ideas that any imitation of Western military technology, industry, and military organization could never match the originals.

In more pragmatic terms, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor because it had the capability to do so. Its fleet was greater than the 7th Fleet of the United States Pacific (though not by any means the entire U.S. Navy). In numerous categories of fighter aircraft, torpedoes, and ships, the Japanese Imperial Navy momentarily outperformed the American Navy in late 1941.

In the view of the Japanese, the US had also lost deterrence since it did nothing when Nazi Germany attacked its main allies, Britain and France, in 1940, the former bombed in fall 1940 and spring 1941, and the latter seized in seven weeks by the Wehrmacht in May 1940.

More specifically, Japan assumed that, with the German army stationed just a few kilometers from the outskirts of Moscow at the time of Pearl Harbor, the Soviet Union would collapse within days. Hitler would thus be free to build his continental dominion and quickly crush the remnants of the once-proud allied resistance. In other words, Japan estimated that if it could claim credit for the inevitable Axis triumph before the war ended, it would be able to seize as much as it could before the prizes were fought over and divided up.

Note that when the Germans signed a nonaggression pact with the Soviet Union in August 1939—while Japan was fighting an allegedly common communist Russian opponent on the Mongolian border—they paid little attention to their de facto ally Japanese concerns.

When the Japanese reciprocated by signing their own nonaggression pact with Stalin in April 1941, just weeks before Operation Barbarossa, the Soviet Union was persuaded that it no longer needed to worry about a second front on its eastern borders and could focus all its resources on the German invader. After April 1941, Japan thought that, whatever the outcome of Germany's and Russia's ties, it could now focus only on the Anglo-Americans, particularly with its navy, which had caught up to British and American sea- and airpower.

All of these arguments were understandable for a hostile state seeking to expand an already powerful Asian Empire into the Pacific. However, such justifications were still based on erroneous reasoning, a racist misunderstanding of history, and a lack of understanding of the American people.

Tokyo had no real appreciation that the United States was already building a second fleet of modern carriers, battleships, cruisers, and submarines that would soon make the American navy larger than all the world’s fleets combined. Indeed, the Americans would launch over 145 aircraft carriers, including over 20 Essex fleet carriers, the most advanced in the world.

Tokyo had no inkling that the anemic Depression-era American economy was capable of rapid expansionary growth. More specifically, the American gross natural product by late 1944 would outpace all five economies of the major combatants—Germany, Italy, Japan, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union—combined.

Ignorance of Innate American Strength

The Americans and the British were the only two World War II countries having the global reach, lift, transport, and resources to effectively fight a two-front war, unlike the Germans, Japanese, or Soviets. Japan, on the other hand, would swiftly discover that its decade-long presence in China was an open wound that drew vital resources from its simultaneous battles with the United States and the United Kingdom.

In terms of the surprise assault on December 7, it is best viewed as the worst of all worlds—conducted well enough to do damage and hence provoke American outrage, but not so much as to impair America's ability to wage war or terrify the American public into submission.

A formidable Japanese Imperial Navy carrier task force traveled undiscovered 4,000 miles to Hawaii, capable of launching 350 combat aircraft from its six fleet carriers. The fleet's ability to travel such a long distance without radio communication and in severe seas at the start of winter, while avoiding all military and trade ships, demonstrated true tactical brilliance.

The procedure itself went off without a hitch. Two waves of carrier-based torpedo and dive bombers sunk five battleships of the US 7th fleet at daybreak on a Sunday morning. Four others were critically injured as a result of the incident. Over 2,300 American sailors and soldiers were slain by the Japanese during a time of peace. The Japanese fleet made it back to Japan safely. There were just 29 aircraft lost, as well as five tiny one-man submarines.

Again, even if tactically brilliant, the Pearl Harbor attack would be a catastrophic strategic failure for Japan. The Japanese navy blocked suggestions for urgently required third and fourth air strikes—necessary to destroy U.S. oil storage and repair shops in the Pacific harbor facilities—so it failed to shut down the port at Pearl Harbor. Pearl Harbor was receiving 7th Fleet ships within days.

The Pacific fleet's three American aircraft carriers stationed at Pearl—Enterprise, Lexington, and Saratoga—were out to sea on December 7 and so safe for the Japanese. Six months later, at the Conflict of the Coral Sea, Lexington's dive bombers would help sink a Japanese carrier and damage others before being lost in the battle. Both the Enterprise and the Saratoga would survive the war and engage in numerous crucial Pacific battles.

If the captains of the relatively old and slow American battleships of Battleship Row had received advance word of the Japanese approach and steamed out to meet the attackers without air cover, American casualties could have been ten times higher—given that all eight battleships would have likely been sunk on the high seas well before reaching the Japanese fleet.

As a result, the Japanese provoked—but did not substantially harm—the one worldwide force capable of not only defeating them, but also dismantling their faraway empire and destroying the Japanese mainland.

What If?

Were there any other strategic options for the war-hungry Japanese? Plenty. European colonial presence in the Pacific was generally minimal or non-existent by 1941. This fact provided the Japanese with possibilities for acquiring resources without having to go to war with the US.

Since June 1940, the triumphant Germans have occupied both France and the Netherlands. Even if the Japanese had simply expanded their newly acquired Indochina concessions—appropriated from the Vichy French in 1940—grabbed the equally orphaned oil-rich Dutch East Indies, and been content with conquering resource-rich, British-held Malaysia and its fortress port at Singapore—while avoiding Pearl Harbor and the Philippines—there would have been little chance of the US joining the conflict even then.

Instead, the Pearl Harbor attack enraged and woke up the Americans to launch the largest economic and industrial renaissance in history to that time. Just four months after Pearl Harbor, the United States had bombed Tokyo with Jimmy Doolittle’s carrier-based medium bombers. Note that at no time did the Japanese Imperial Navy have the ability to bomb any major U.S. continental city. By August 1942 American forces were on the offensive at Guadalcanal and were already gearing up for a two-pronged island-hopping trajectory to Tokyo.

In contrast to the very instantaneous Anglo-American cooperative preparation in December 1941, Adolf Hitler was completely astonished by the Japanese strike and was not consulted about it. Indeed, Hitler appears to have had little or no knowledge of the location of Pearl Harbor. Nonetheless, he was overjoyed with the news, especially considering his unhappiness with the Kreigemarine's surface fleet's poor performance.

Nazi Germany erroneously expected that Japan would encircle and destroy the British and American Pacific fleets, diverting alliance forces to Asia and the Pacific. Above all, the newly enlarged assault on America was planned to allow Nazi U-boats to finally sink American trade ships bound for the United Kingdom as soon as they departed their East Coast ports.

Instead, all Hitler earned from Pearl Harbor was an enemy more powerful than his existing opponents and an enemy alliance with huge manpower and economic resources. The new Allies—Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States—enjoyed collectively a population double that of the Axis nations, vastly more natural resources, and three times more men and women in arms.

The Yamamoto Myth

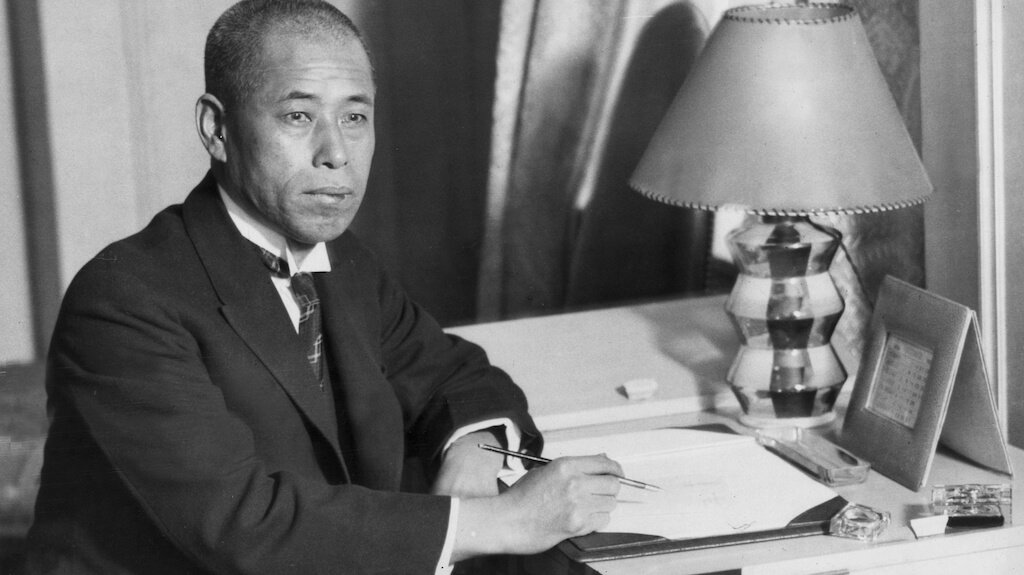

Admiral Yamamoto, the mastermind behind the assault on Pearl Harbor, is sometimes romanticized as a mythological, almost reluctant warrior who knew all along that the operation would awaken a sleeping monster. As a result, he accepted the fact that he would only be able to run wild for six months before being overrun by American industry, technology, and righteous outrage. Yamamoto, according to this historically flawed account, was a tragic hero tasked with devising an unachievable plan for defeating a much larger and stronger United States.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Yamamoto himself agitated for the surprise Pearl Harbor attack. And he even threatened to resign if a skeptical General Tojo and Emperor Hirohito did not grant him a blank check to bomb the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Hawaii, a diversion of resources many in the Japanese military felt was unjustified, especially with the ongoing and increasingly expensive quagmire in China.

While the Japanese army lacked the firepower, armor, and mobility of Western ground forces, Yamamoto successfully claimed that Tokyo's imperial air and naval power had already attained parity—both in terms of the quality of their weapons and the quantity of ships, aircraft, sailors, and airmen.

In terms of 1941-era weapons, Japan was frequently superior to both the Americans and the British—at least if it attacked before the two Western countries had completely rearmed. Yamamoto felt that by winning, the devastated Americans would be discouraged from attacking a new broad Japanese Pacific empire. Washington was rumored to be considering suing for a ceasefire, acknowledging Japan's former colonial holdings.

To summarize, the strategic folly of a stunning but short-lived triumph at Pearl Harbor was partly explained by Yamamoto's immense ego, tactical skill, and strategic incapacity, as well as Japanese pride. To be fair, no student of military readiness, economic resources, or social organization could have predicted that a relatively vulnerable and isolationist United States, still reeling from recurring cycles of depression, would fight simultaneously across the Pacific and Europe with a 12 million-strong military, the world's largest economy, and the world's most formidable weapons, including Essex class fleet carriers and Balao submarines, in less than four years.

All of this happened 80 years ago this December, when a sophisticated Japanese Empire made the mistake of attacking the United States during peace.