More On: books

Matt James' New Book Details What Didn't Make the Cut on 'The Bachelor'

Why Jamie Lynn Spears Couldn't Tell Sister Britney About Her Teen Pregnancy

Emily Ratajkowski's 'My Body' Book: 'Blurred Lines' Bombshells and More

Will Smith Recalls Falling 'in Love' with Former Costar Stockard Channing

Elise Museles Shares Nutrition and Diet Secrets in New Book 'Food Story'

The teen drama series “Gossip Girl” shone light on the sexy scandals and lavish lifestyles of Manhattan’s elite prep schools when it premiered in 2007. But for Upper East Side native Wil Glavin, who was on the verge of high school at the time, it barely scratched the surface. “‘Gossip Girl’ didn’t go far enough. …

The teen drama series “Gossip Girl” shone light on the sexy scandals and lavish lifestyles of Manhattan’s elite prep schools when it premiered in 2007.

But for Upper East Side native Wil Glavin, who was on the verge of high school at the time, it barely scratched the surface.

“‘Gossip Girl’ didn’t go far enough. They had to keep it more PG-13,” said Glavin, who just self-published a novel, “The Venerable Vincent Beattie,” based on his own tween and teen years at posh prep schools. “My book is more R-rated.”

Glavin, who started writing the tome in January 2019 and finished it after being furloughed from his assistant job at Marvel Entertainment, used his alma maters as inspiration: Buckley, the all-boys academy on East 73rd Street attended by Roosevelt and Rockefeller scions; and the co-ed Columbia Grammar and Preparatory School on the Upper West Side, where celebrity alums include Herman Melville, ex-Time Warner CEO Steven Jay Ross and actress Ally Sheedy. Gov. Andrew Cuomo spoke at Columbia Prep’s 2017 graduation; Barron Trump was enrolled there until his move to Washington.

A self-described introvert, Glavin said his protagonist is “a more extreme version” of him, but Vincent’s journey through the wild world of New York City’s prestigious private schools is based on Glavin’s real life.

“A lot of stories I got were just from listening to gossip in the student lounge for four years,” Glavin told The Post.

His parents, a bond salesman and a stay-at-home mom turned marketing executive, were disciplinarians when Glavin was younger.

“My teachers were very strict, and my coaches were very strict,” said Glavin, a 2016 Tufts graduate. “Elbows off the table, chew with your mouth closed. I took etiquette classes … People would always ask me if I had a military background because I am so rigid.”

His sheltered upbringing led to shock at the social scene he observed as he grew up among a well-heeled set.

First came over-the-top bar and bat mitzvahs — Ciara performed at one, Glavin said, and Sean Paul at another. Later, there were the urban equivalent of house parties, which at their most extreme featured hard alcohol and drugs like pot and cocaine.

“In Manhattan, they’re apartment parties or penthouse parties,” said Glavin, who set a scene in “Vincent Beattie” at a particularly debauched one. “There are people hooking up on couches, and they are drinking and smoking cigarettes out the window. And these are the nicest apartments in New York City, with $30,000 tables and $100,000 chandeliers.”

Not everyone took part in these shenanigans. Glavin was a guest at a handful of such soirees, but took his first drink as a high school senior and has never tried drugs.

“I’m glad I was able to go to as many things as I did, because it gave me a lot more material and ammunition,” he said adding that only a small percentage of people he knew were extreme or dangerous partiers.

“These parents would say, ‘Don’t do anything I wouldn’t do,’ and they closed the door,” he added. “The houses would be stocked with nice alcohol and champagne, and people played beer pong. It was so crazy to me.”

Flagrant spending by some classmates also went largely unchecked.

“Kids had their own credit cards and spent ridiculous amounts on parties or alcohol or traveling,” Glavin said, adding that some bought fake IDs for clubbing and there often was “next to zero supervision.” “Girls and guys would go to Madison Avenue [to shop] during a free period, going to any restaurant and not even caring how expensive certain things are. The money wasn’t theirs, so they spent whatever they wanted.”

Signs of wealth cropped up in small ways, dividing the mere haves from the have-a-lots. Some students, for example, had personal chauffeurs.

“I always have that image of walking out to Central Park West [by Columbia Prep] and seeing five or six blocks straight, lined with black or white Escalades,” he said.

A highlight of the private school party circuit occurred over spring break, when seniors from different schools organized a trip to Paradise Island in the Bahamas. About 35 to 40 kids per school, Glavin said, flew down for the week.

“No chaperones, no teachers and no parents. It gets so insane down there because the drinking age is 18,” said Glavin, who added it cost between $1,500 to $1,800 per person for five nights at Atlantis, an all-inclusive resort. “We would get to the airport, and people would just buy handles and drink their faces off in their hotel room. There were nightclub parties every night.”

Glavin, who tagged along like “a fly on the wall” because his parents loosened up following their separation when he was 14 (and even paid for him to go to the Bahamas), penned two juicy chapters about the annual hedonistic underage getaway.

He said he thinks “parents back home understood what was going on to an extent. They knew they were drinking and having sex, and no one seemed to care or mind. There was a ‘boys will be boys’ and ‘girls will be girls’ mentality.”

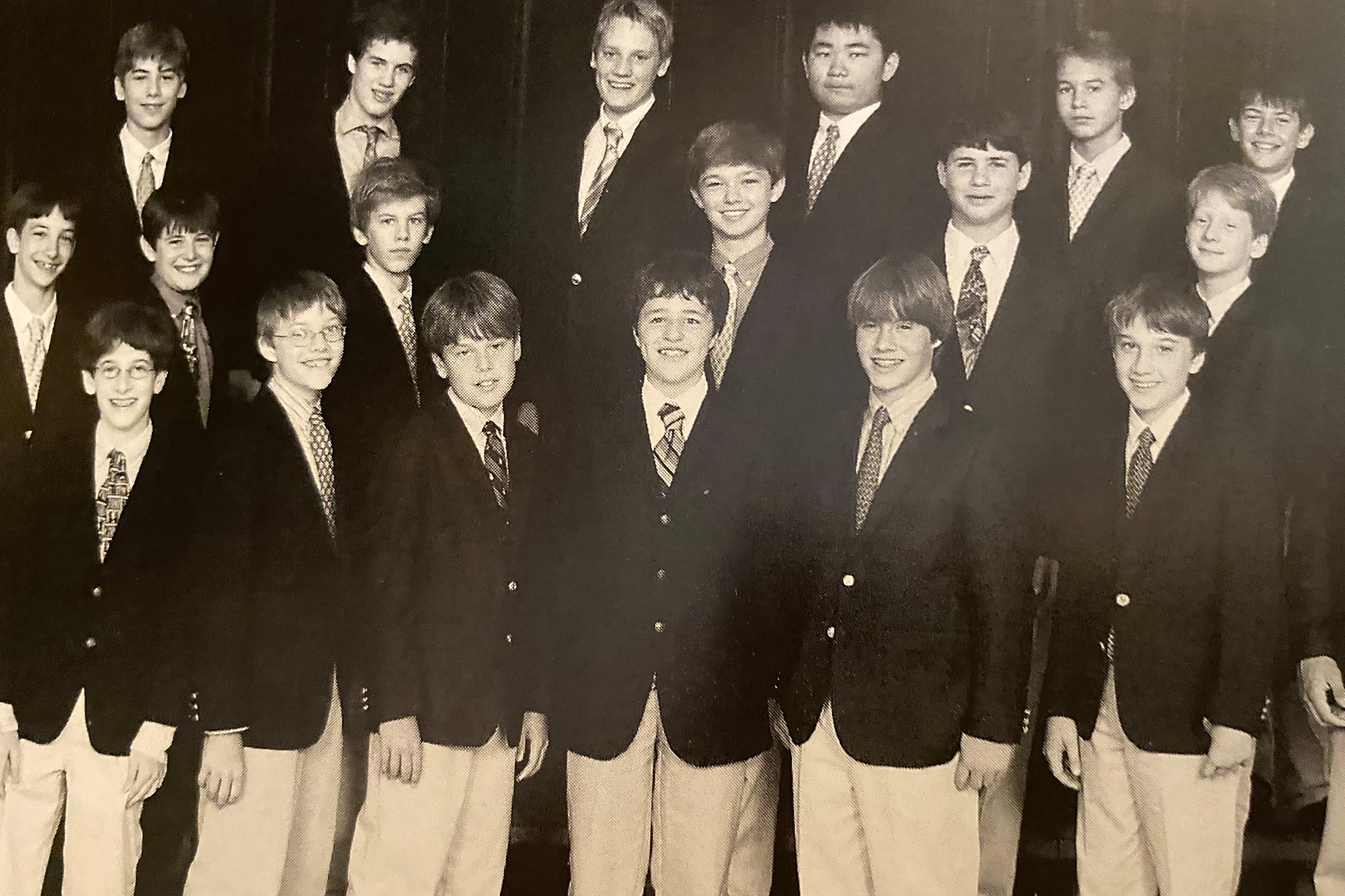

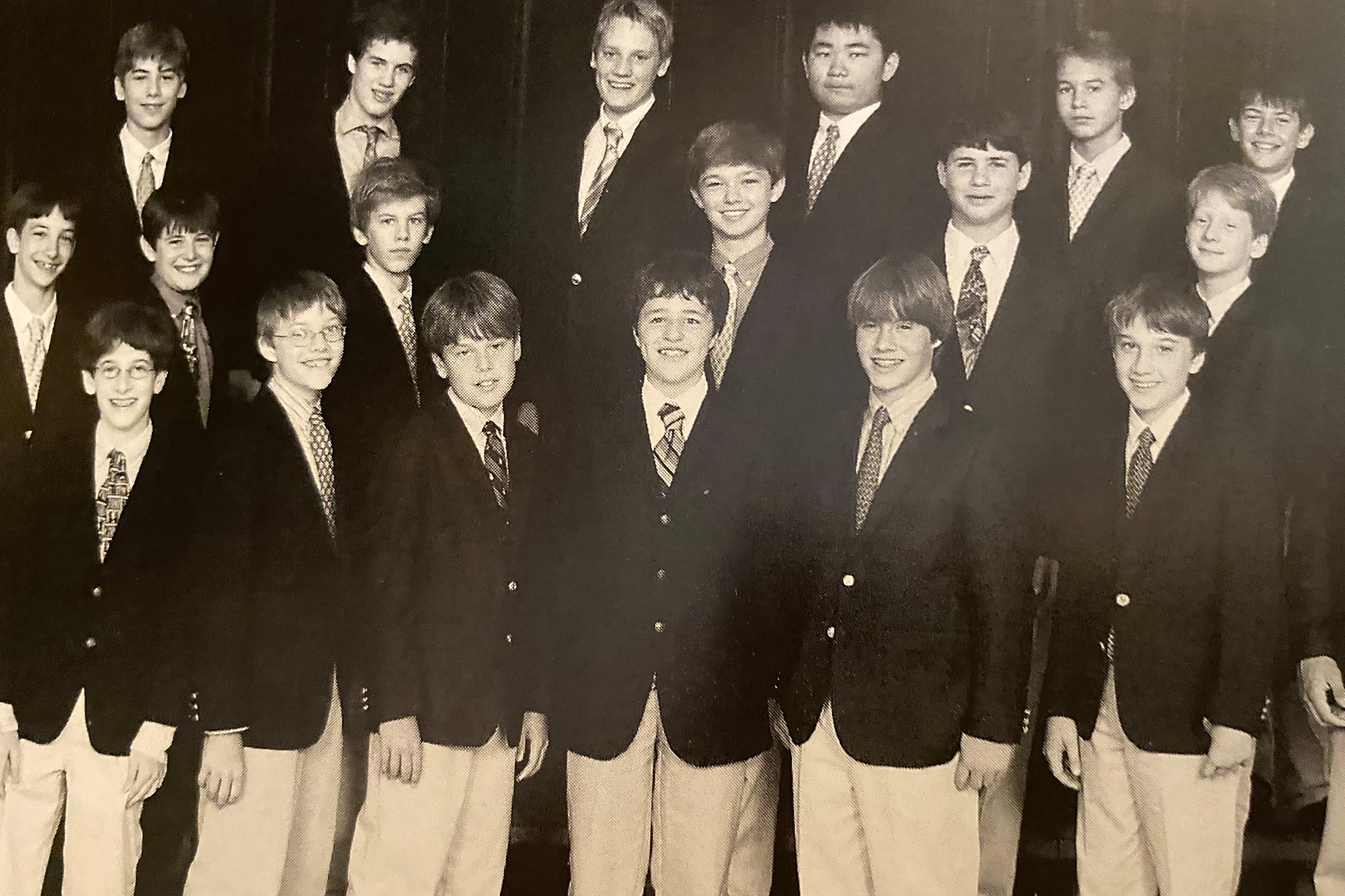

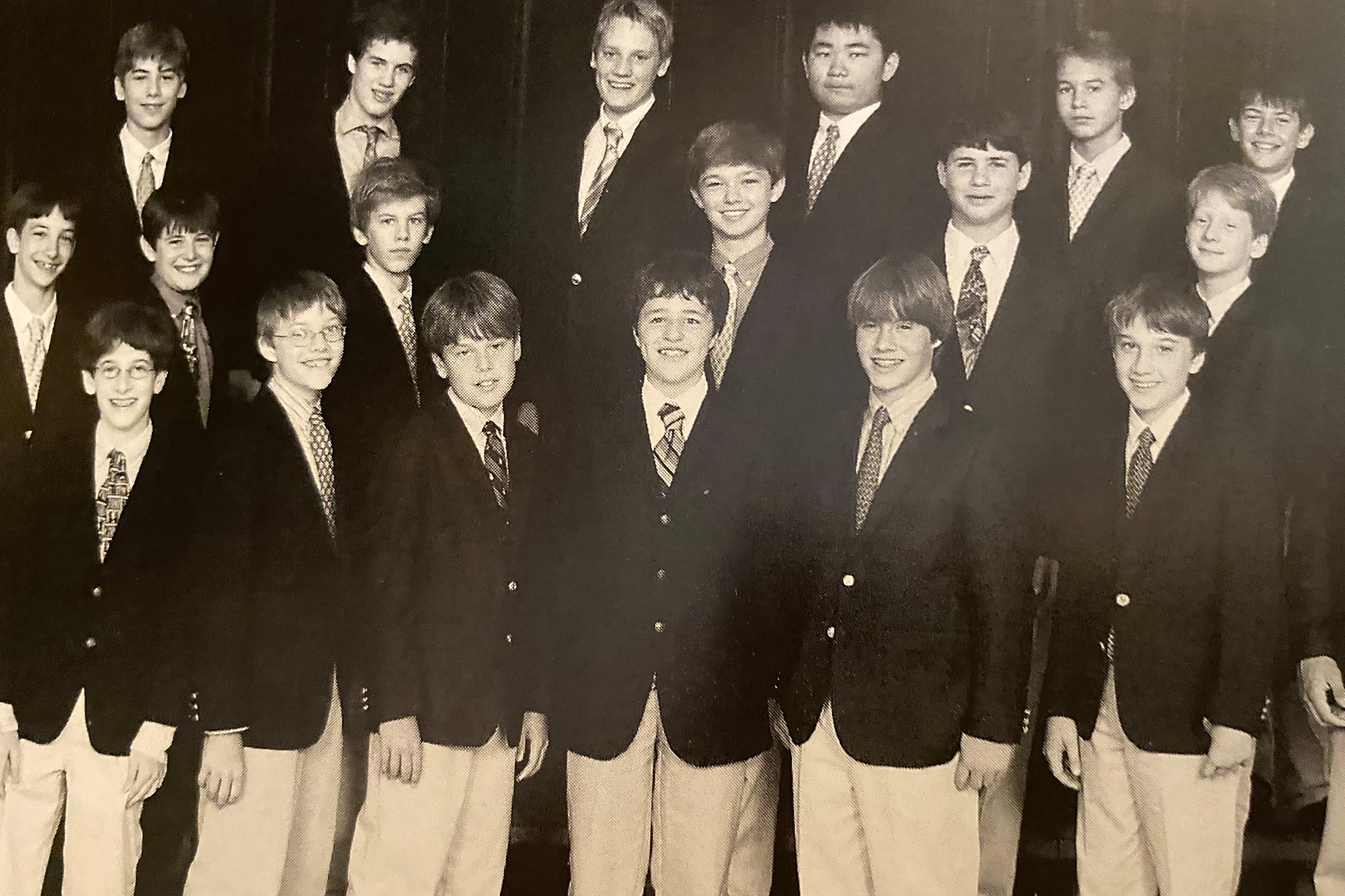

Wil Glavin’s class photo.

Courtesy

Wil Glavin’s class photo.

Courtesy

Wil Glavin playing piano.

Courtesy

Wil Glavin in on the Paradise Island trip.

Courtesy

There was a lack of consequences for students who did break rules, Glavin said, in part because parents were often not around to enforce punishments because they were working or traveling.

“If you’re getting grounded by parents, and they happen to be overseas, or they’re working until 11 p.m., it never seemed to prevent people from going out,” he said. “They’d say, ‘My parents are really pissed at me, and they threatened to take away my credit card.’ ”

Even if mom and dad happened to be home, there were ever-present housekeepers, leading to some creative romantic trysts and “a lot of Central Park hookups,” Glavin said.

“You’d ask your friend, ‘If your parents aren’t home, can we go use [your apartment] for 30 minutes or use it for an hour? Do you have siblings? Do you have a reliable doorman who won’t tattle on you or won’t tell your parents?,’ ” he said. “In a rare case, if you are very well-off, there’s getting a hotel room, but that wouldn’t happen until you’re 18 or so.”

The privileged practices of a selective New York City enclave are laid bare in his book, Glavin said, which can allow a much wider audience to appreciate them.

“I hope it helps the introvert, helps the loner, helps the person who doesn’t feel like they fit in,” he said. “It’s relatable for current high school and college students, it’s nostalgic for people post-college, and for parents and teachers, it’s informative. It’s like, ‘Wow, I had no idea it was like this.’ “