More On: Great Depression

The Patsy of the Great Depression

The 1920-1921 depression was a textbook example of how to handle an economic downturn

Why Did Roosevelt's New Deal Spending Fail to Lift the American Economy?

What Caused the Great Depression?

Coronavirus may lead to worst global recession since Great Depression: IMF

Popular history says that ending the gold standard, which made it possible for the government to spend a lot of money, ended the Great Depression. As usual, most people are wrong about history.

In 1913, the US government created the Federal Reserve System and put it in charge of the money supply. This was done to protect fractional reserve banking and find someone to buy its debt. From July 1921 to July 1929, the Federal Reserve made 62 percent more money than there was, which led to the crash in late October. For the first time in American history, the US government took action as part of an aggressive "do something" program. They did this in a number of ways during the 1930s, first under Herbert Hoover and then more so under Franklin D. Roosevelt. Robert Higgs explains in detail how this didn't make things better or speed up the recovery, but instead made the Great Depression worse.

The above explanation is not, of course, the most common one. In common thinking, the fact that the international community stuck to a gold standard was one of the main causes of the Great Depression, or at least made it worse. Barry Eichengreen, an economist, made this idea very popular. The Wikipedia page for Eichengreen has a summary of Eichengreen's thesis by Ben Bernanke:

The proximate cause of the world depression was a structurally flawed and poorly managed international gold standard. . . . For a variety of reasons, including among others a desire of the Federal Reserve to curb the US stock market boom, monetary policy in several major countries turned contractionary in the late 1920’s—a contraction that was transmitted worldwide by the gold standard.

Why would a contractionary monetary policy be harmful? Because fractional reserve banking is a house of cards, and such policy risked toppling it. When inflation is exposed and the gold is not there, bankers do the Jimmy Stewart scramble. In Bernanke’s words, “what was initially a mild deflationary process began to snowball when the banking and currency crises of 1931 instigated an international ‘scramble for gold.’”

The State’s Classical Gold Standard

The classic gold standard, which was used in the West from the 1870s to 1914, was a fiat gold standard, which means that it worked at the state's whim. When the government didn't like how the gold standard was working, gold convertibility was put on hold. This let banks back out of their promise to exchange paper money and deposits for gold coins on demand.But even when the government was in charge, the old gold standard kept inflation in check. Gold was used as money, and different weights of gold were used to name different currencies. For example, a dollar was the name for one-twentieth of an ounce of gold. A dollar was not money, so it was not backed by gold. A dollar was sometimes used in place of the real thing. The only thing that governments and central banks could directly inflate was their currencies, but if they did it too much, they would lose gold to countries that did not inflate as much. In other words, they couldn't stick to the old gold standard and print a lot of money at the same time.

With the start of World War I, the governments of the countries that were fighting each other told their central banks to stop exchanging their currencies for gold. With the gold standard, there could not be a long war because gold could not be made on demand like money could. By making their currencies worth more than they were worth, governments killed not only millions of people but also the old gold standard. Like I've said before, "Sound money had to die before so many men could die."

After the war, the inflation of money and prices gave governments a choice: they could either go back to the old gold standard with lower exchange rates or go back to the pars that were used before the war. In order to make London the financial center of the world again, Britain chose to go back to its prewar par of $4.86. For this to work, other countries, especially the United States, had to give up some money.

The New Gold Standard

At the Genoa Conference in 1922, representatives from thirty-four countries met to talk about money. At that time, the government was in charge of the structure of the monetary order. It was clear what was wrong. Gold let down governments when they needed money the most (to go to war). Gold had shown itself to be very unpatriotic. On the other hand, paper money could not say no, just like the "girl from Oklahoma." No matter what the government planned, paper money supported it. So, the problem wasn't that there was too much paper; it was that there wasn't enough gold.Gold's fatal flaw was now that it was hard to get. But the economists in charge of its future weren't ready to say that the money people had been using for the past 2,500 years was suddenly bad for their economy. So gold played a small supporting role, but its name was big and bold on the sign for the economists' new plan, which they called the "gold exchange standard." Here's what they agreed to:

- The United States would stay on the classical gold standard. This meant people could exchange $20.67 in currency and coin at the Treasury for a one-ounce gold coin. The gross inconvenience was intentional.

- Britain would redeem pounds in gold and US dollars while other nations would pyramid their currencies on pounds.

- Britain would redeem pounds only in large gold bars. Gold was thereby removed from the hands of ordinary citizens allowing a greater degree of monetary inflation.

- Britain also pressured other countries to remain at overvalued parities.

This international plan to cause inflation brought gold along for the ride to make it look stable and important. When the plan fell apart, as it was bound to, gold was used as an excuse.

Gold Gets a Prison Sentence

Keynesians and other monetary scientists claim to have a smoking gun.

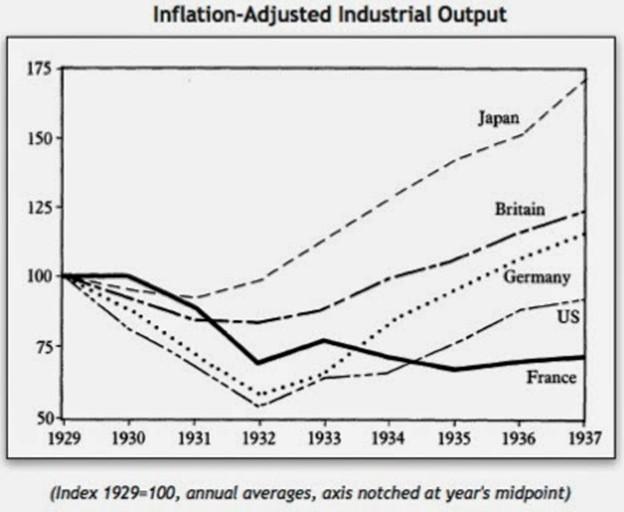

Source: Barry Eichengreen, “The Origins and Nature of the Great Slump Revisited,” Economic History Review 45, no. 2 (May 1992): 213–39.

In this chart, which was copied by Robert Murphy from a paper by Barry Eichengreen, each country's output is set to 100. Measurements after 1929 are given as a percentage of how far they are from the 1929 standard.The chart shows in what order countries got rid of gold. Japan was the first country to go gold, followed by Britain, Germany, the United States, and finally France. At first glance, the chart seems to show that prosperity and an unredeemable currency go together. But pay attention. From 1932 to 1933, industrial production went up a lot in both Germany and the US. The US didn't "go off gold" until almost the middle of 1933, but industrial output was already going up in 1932.

As Murphy points out, the chart has some mistakes, but it is said to show the positive effects of devaluation over time. But the Great Depression didn't end in 1937. Throughout the 1930s, unemployment rates stayed in the double digits.

In the past, depressions ended in two or three years, and people's gold was never taken away. Why did gold become a big problem all of a sudden in the 1930s?

What did it mean for someone to "go off gold"? It meant that US citizens who didn't follow Roosevelt's order to turn in their gold would have to pay a $10,000 fine and spend ten years in prison. This was the penalty for having the money that tens of millions of people in the market chose. Roosevelt's order hurt people all over the world who had assets worth dollars and thought they could trade them for gold.

Also, should it be a surprise that the economy got better after "going off gold"? Murphy says that dropping the gold standard is like a homeowner saying, "I'm going off my mortgage." He tells the person who owns his mortgage, "I'm not going to pay you anymore. And I have more guns than you do, so tough."

Since the homeowner no longer has to pay a mortgage, it makes sense that their standard of living goes up. Getting ahead in the short term by getting out of some contractual obligations does not prove that those obligations were not valid.

Conclusion

The government will never stop being able to print money (counterfeit). As we've seen, a gold standard makes it hard for the government to raise prices.The only way to limit what the government can do to us is to have a free-market monetary system without a central bank.

[This article originally appeared in the January 4 edition of Lewrockwell.com.]