More On: los angeles angels

Yankees acquire Andrew Heaney from Angels before MLB trade deadline

Stephen A. Smith apologizes for Shohei Ohtani comments: ‘I screwed up’

Stephen A. Smith: Shohei Ohtani ‘harming’ baseball because he ‘doesn’t speak English’

Yankees-Angels game postponed due to rainy forecast

Aroldis Chapman implodes as Yankees lose crusher to Angels

Is Shohei Ohtani really the new Babe Ruth, though?

More from:

Ken Davidoff

Yankees desperately need to shake up their roster

Why reeling Yankees are now staring at 'important game'

Aaron Judge becoming type of challenge Yankees will embrace

Yankees' little mistakes adding up against Red Sox

These Yankees are daily roller-coaster ride

BOSTON — On Oct. 1, 1933, at the original Yankee Stadium, the Yankees defeated the Red Sox, 6-5, behind a complete-game effort from Babe Ruth, who supported his own efforts with a home run.

Nearly 88 years later, the sequel to that event will occur Wednesday night when Shohei Ohtani takes the mound for the Angels at the new Yankee Stadium, by which point he might already have knocked a ball or four out of the park in his other role as the team’s primary designated hitter.

Is Ohtani really the new Babe, though? Or might we find a better comparable to this generational talent, the most exciting and unique professional athlete on this planet, by looking back shorter and wider?

“The only person I can compare him to is the whole phenomenon of Bo Jackson,” Mark Gubicza, an Angels television color analyst for Bally Sports West, said last week in a telephone interview. “He’s like a rock star right now.”

Ohtani, 26, is “an absolute freak of nature,” said Michael King, who will start Monday night’s series opener for the Yankees.

Added Yankees manager Aaron Boone, whose grandfather Ray made his major league debut in 1948, the same year The Sultan of Swat died, “The ability to dominate on both sides of the ball is something none of us have really ever seen.”

The reference to domination serves as no exaggeration, as Ohtani ranks among the major league leaders in home runs (25), RBIs (59) and OPS (1.031) while posting a 2.58 ERA in 11 starts totaling 59 ¹/₃ innings. No wonder the Yankees wanted him so badly during the 2017-18 offseason, when he chose the Angels.

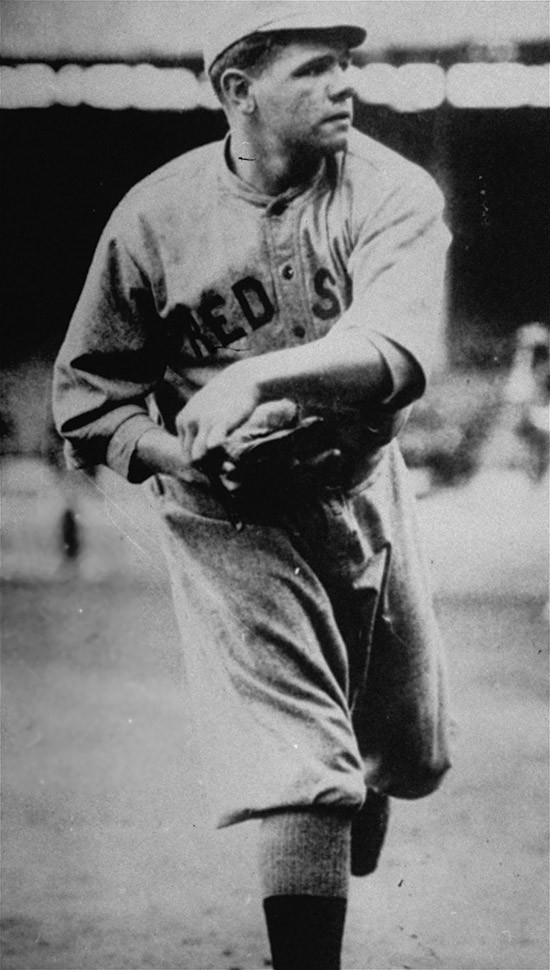

Ruth registered two seasons with the Red Sox, 1918 and 1919, in which he put up above-average numbers as both a hitter and a pitcher, more the former than the latter. When he became a Yankee in 1920, he shifted primarily to an everyday player in right field; he pitched only five times in a Yankees uniform.

And therein lies the primary difference between The Bambino and his baseball descendant, the two men born 99 years apart: Only one of them embraced this duality.

“He clearly wanted to move out to the outfield,” Jane Leavy, author of the 2018 Ruth biography “The Big Fella,” said of her subject in a telephone interview. “It occurred at a time due to the draft [for World War I]. With all the players that [Red Sox manager Ed] Barrow was losing, he needed outfielders. And then when he needed pitchers, he wanted Babe Ruth to come back in and pitch. And I don’t think Babe Ruth really wanted to do it very much once he got a taste of frolicking in the outfield.”

Whereas Ohtani, who pitched and hit for the Nippon Ham Fighters in his native Japan, made it clear to interested Major League Baseball teams (all of them) as a free agent that he wouldn’t commit unless the employer committed to letting him pursue his dream of excelling at both. The Angels blessed this even after Ohtani underwent Tommy John surgery in October 2018.

Which brings us back to Bo, who won the Heisman Trophy as a running back for Auburn, saw his name called as the first-overall pick of the 1986 NFL Draft (by the Buccaneers) and proceeded to ditch the Bucs to sign as an outfielder with the Royals, who selected him in the fourth round of that year’s baseball amateur draft.

“Bo, you talk about a five-tool player across the board and he was the ultimate,” Art Stewart, then the Royals’ director of scouting and now a senior adviser to general manager Dayton Moore, said in a telephone interview. “He ran a 3.6 [from home plate to first base] from the right side. [Mickey] Mantle was 3.6 from the left side. I thought [Roberto] Clemente had the greatest arm, but Bo had a Clemente arm or probably better. He had power I haven’t seen equal. You talk about everything we look for in baseball and he was the best at it.”

Jackson made his major league debut that same year, 1986, and as Stewart put it, “the sad thing was he learned to become a ballplayer in the big leagues.” He didn’t shine immediately. Yet in 1989, he started in left field and hit leadoff for the American League in the All-Star Game and earned the Midsummer Classic’s Most Valuable Player honors after launching a leadoff homer against National League starter Rick Reuschel.

By that game, arguably his signature moment as a baseball player, Jackson had done the same in the NFL, steamrolling acclaimed Seahawks linebacker Brian Bosworth while scoring a touchdown for the Raiders in 1987, his rookie NFL season. As per a deal Jackson cut with the Raiders after they drafted him in ’87, he clocked the full MLB campaign with the Royals and joined the Raiders in the middle of the football schedule. He played in the 1991 Pro Bowl, becoming the first (and only, still) professional athlete to be named an All-Star in the two sports. While Jackson’s contemporary Deion Sanders also enjoyed success in both worlds, memorably playing in a Falcons game and Braves playoff game on the same day in 1992, he never possessed a baseball ceiling like Jackson’s.

Gubicza, a starting pitcher who played alongside Jackson with the Royals, attended some of Jackson’s Raiders games in Los Angeles (their home at the time). He recalled: “I used to go in the locker rooms after the football games in the old [LA] Coliseum and think, ‘This guy is a freak. There’s nothing you can do to him.’ ”

As a broadcaster now, Gubicza experiences similar sensations watching Ohtani work: “He threw six innings and struck out 10 [June 4 against the Mariners]. My legs, my ribs, my shoulder would be sore the next day after doing that. The next day, he hit a first-pitch home run. How is this possible? I’d be doing my long-distance running and lifting some weights and that was a struggle, and here he is, hitting a home run. I’m scratching my head all day long thinking, ‘How is he doing this?’”

“There is such a thing as neuromuscular genius,” said Leavy, who wrote about this concept in “The Lost Boy,” her Mickey Mantle biography. “It isn’t just the physiological skill. It’s something in the way the brain is wired that allows them to get places and do things that nobody else has been able to do. It certainly appears that Ohtani may be one.”

“It’s a great comparison you’re making, him and Bo,” Stewart said of Ohtani. “He’s got one advantage over Bo and that is he can pitch.” Of course, Jackson could run for nearly 1,000 yards in a half-season against NFL defenses, a feat Ohtani — who will compete in next month’s Home Run Derby — appears unlikely to attempt.

Jackson’s unicorn reign proved pretty short, a 1991 football hip injury ending his gridiron career on the spot and ceasing his status as a baseball star; he played in parts of 1991, 1993 and 1994 for the White Sox and Angels before retiring after the ’94 work stoppage at age 32.

Ohtani’s staying power remains in question. Said Leavy, comparing Ohtani to Ruth: “Let’s see where he’s at in 20 years. The comparisons are as inevitable as they are fallacious at this point because you don’t know where he’s going to end up.”

Fair enough. At this moment, though, someone special, reaching new heights, will be in The Bronx. “There could be a Mickey Mantle moment if he gets a hold of one,” Gubicza said.

Yes, this guy evokes the greats, over and over. Whoever he resembles the most, it’s clear that, down the road, it will be an honor for someone else to be likened to Shohei Ohtani.

This story originally appeared on: NyPost - Author:Ken Davidoff