More On: hardball

Cubs’ selloff may change how we view the Yankees: Sherman

Making sense of Yankees’ underwhelming draft history: Sherman

Shohei Ohtani, plenty of Mets and Yankees take midseason awards: Sherman

Yankees have to seriously consider these potential trades: Sherman

How to solve MLB’s maddening mound visit problem: Sherman

This is cheating, against the rules on the book as much as loading a bat with Super Balls.

More from:

Joel Sherman

Yankees' stubbornness taking its toll: Sherman

Aaron Hicks, Luis Severino contracts are Yankees disasters: Sherman

Yankees can’t hide from AL East reality any longer: Sherman

Yankees' center field conundrum has few appealing options: Sherman

Yankees weak link Jameson Taillon needs to pick it up: Sherman

Perhaps Major League Baseball was on an inevitable decline in the national consciousness and nothing could have prevented it becoming more of a local passion.

But what steroids did to home run numbers around the turn of the century, in particular, hastened this. Because in no sport do statistics matter more. Yes, the NFL is king, but how many fans know, for example, how many yards Emmitt Smith rushed for? The NBA is ascendant, but does anyone have any clue how close LeBron James is to overtaking Kareem-Abdul Jabbar as the all-time leading scorer.

We did know, however, what 60 and 61, and 714 and 755 were, and meant. Many fans could name everyone who hit even 50 homers in a season, and many more knew the 500-homer club. Then all of that was distorted unnaturally to that point you can ask even a strong fan how many homers Barry Bonds finished with and get a blank stare. When a player approaches 500 homers now, the luster (and interest) is depleted.

As an industry, by not uniting to stop the cheating sooner — and really not until Congress applied outside pressure — MLB lost among its most treasured assets: the value and significance of home run achievements.

We now threaten to do the same with pitching. My MLB Network colleague Ron Darling believes multiple pitchers in 2021 are going to sink beneath Bob Gibson’s Live Ball Era record ERA of 1.12 from 1968. Tom Seaver’s half-a-century-old record for most consecutive strikeouts (10) is under assault regularly. Jacob deGrom struck out nine in a row in April, and what should shake everyone involved is how little public traction that achievement received.

Topping the record for 20 strikeouts in a game (if a pitcher is actually allowed to go deep enough) is in play. There already have been six no-hitters thrown this season, which has raised concern whether it is not as thrilling to watch one any longer. Every league, team and collective strikeout record is going to be smashed.

We have been trending this way for a decade. Still, this — like, for example, the single-season homer record going from 61 to 70 — has the feel again of the non-incremental and the unnatural. We learned with steroids that when it is too good to be believed, well … And there is now an industry focusing more seriously on the abundance and advance of illegal sticky substances overtaking the game and distorting the pitcher-hitter confrontation. A cottage industry has grown from pine tar to thickened sunscreens to now concoctions so sticky that people in dugouts say that when the stadiums were empty you could hear the friction as the ball left a pitcher’s fingers.

We have learned what extra revolutions per minute can mean to movement on breaking pitches and ride in the zone on fastballs, ushering in a revolution of revolution — and the hunt (legal and illegal) to gain more.

Action is needed against the illegal. Now. An important step was to come Wednesday and Thursday in New York when owners met in person for the first time since the COVID-19 outbreak. Key to the agenda was updating teams on what has been discovered over the first two months as MLB (as promised) collected baseballs and examined what was on the surface plus studied data such as spin rate, video and took information from monitors at ballparks with eyes out for cheating.

MLB believes it has a strong feel for what is being used, by whom, how often and to what effect. Multiple sources said to anticipate action.

Here’s what I think should be done: Like with COVID testing, redact the name of teams and individual players, but in the report state how many clubs and pitchers have used illegal substances, what the substances are and what that did to rpms. Then pick a start date, like July 1, to state that umpires are being ordered to aggressively check for foreign substances, and if one is proven to be used, then not just the pitcher, but the pitching coach, manager and head of baseball operations too will all be suspended for 10 games (the length Michael Pineda was suspended in 2014 for having pine tar on his neck).

The suspending of coach, manager and GM will prevent the Sergeant Schultz-ing of the issue, like steroids, when all in leadership claimed to not know what was going on. You better make it your business or you get suspended, too.

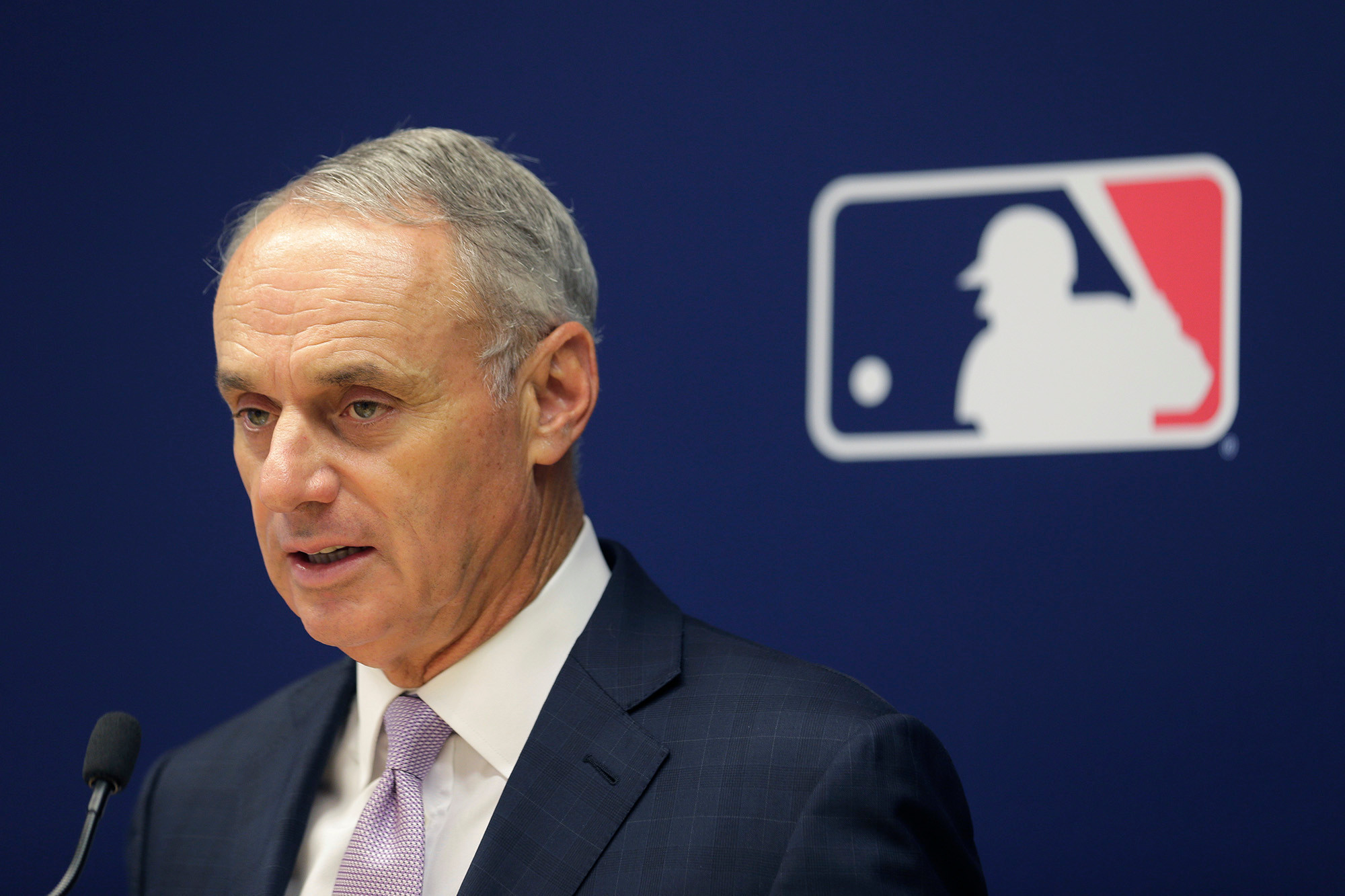

Rob Manfred is going to have to be the one to be the face of this. We know managers are not going to challenge the other team in fear of losing credibility in their own clubhouse because they have cheaters. The hitters have gotten bolder in claiming a problem, but none wants to be seen as a narc in naming names in baseball’s version of the Thin Blue Line.

But the players — not just hitters, but pitchers — and the union should, at minimum, not block such strong action. They really should encourage it. They are all stewards of the game, too, and know what a lingering impact not acting in a unified way on steroids damaged credibility, fan interest and historic records. Hurting the sport, hurts all. And like survey testing for steroids not deterring users in 2003, the announcement by MLB that it was going to investigate the sticky issue has not deterred enough cheating. Many who have been in dugouts this year privately tell me that the malfeasance is blatant.

And this is cheating, against the rules on the book as much as loading a bat with Super Balls. By cracking down for half a season beginning July 1, MLB can gain half a season of information to see how much that helps with the huge problem of too many strikeouts and not enough balls in play.

It will not be a panacea. The hitter-pitcher ecosystem has switched too strongly to the pitcher for many reasons — mostly legal. But before rules are changed to, for example, move the mound back a foot or ban shifts, let’s better enforce an actual written rule. Let’s not let cherished stats and achievements be further debased in the sport that honors them most. Let everyone involved in the game see the big picture — in a way they did not while protecting their own turf in the bad ole steroid days — and unite (you know, stick together) for the good of the overall sport.

This story originally appeared on: NyPost - Author:Joel Sherman