More On: happiness

Risk-taking behavior has a unique and complex brain signature

How the Stoics can help us get through lockdown

How to relax: Learn about the lost art of rest

Money impacts happiness more than previously thought, study finds

Who is most at risk for work addiction?

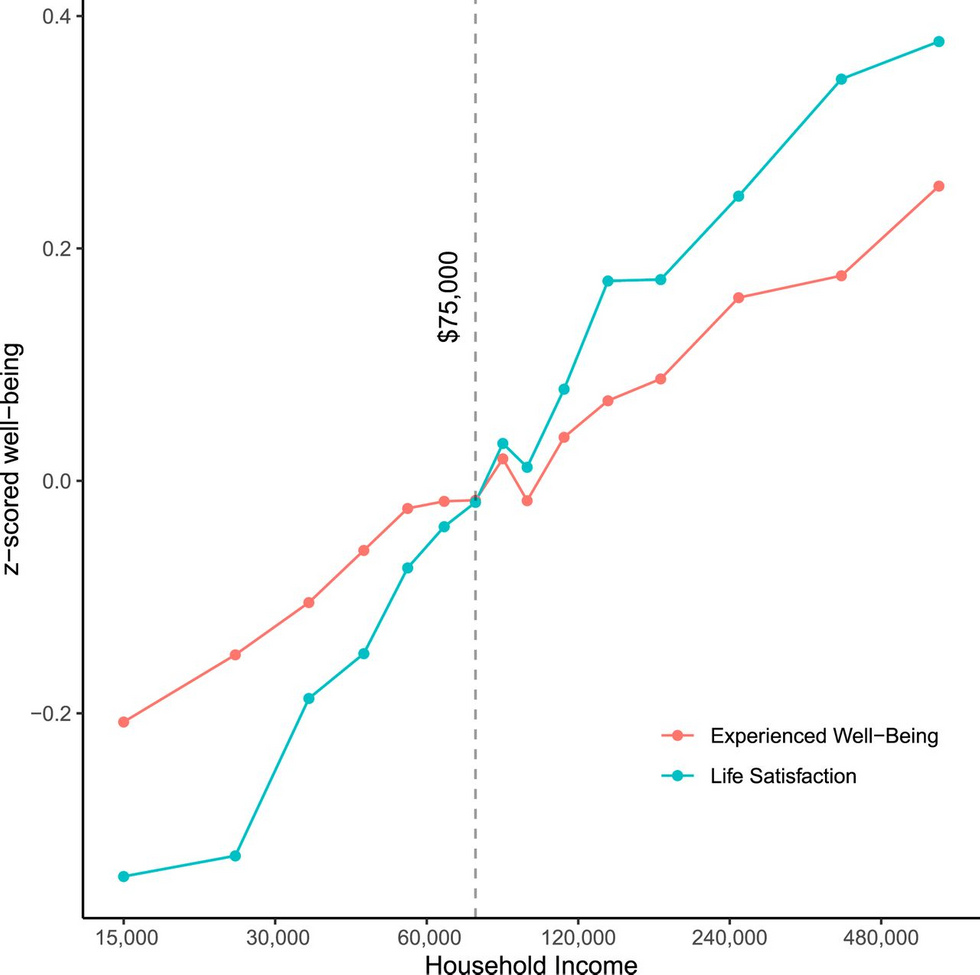

A new study casts doubt on previous research showing that emotional well-being plateaus at an income of $75,000 per year.

- A new study examined how income affects experienced and evaluative well-being, which are two measures researchers commonly use to evaluate happiness.

- The results showed that both evaluative and experienced well-being tend to increase alongside income.

- Still, the results don't suggest you should assign more importance to money, or tie your ideas of personal success to it.

Can money buy happiness?

In 2010, a Princeton University study added nuance to that adage by showing that money does indeed affect happiness, but it stops mattering after you're making about $75,000 a year. People who earned less than that amount tended to report lower levels of emotional well-being, potentially because of stress related to meeting basic needs. But when earning more than $75,000, everyone's more or less equally happy.

However, new research casts doubt on those widely cited findings.

"It's a compelling possibility, the idea that money stops mattering above that point, at least for how people actually feel moment to moment," Matthew Killingsworth, a senior fellow at University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School, told Penn Today. "But when I looked across a wide range of income levels, I found that all forms of well-being continued to rise with income. I don't see any sort of kink in the curve, an inflection point where money stops mattering. Instead, it keeps increasing."

Income and well-being

Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the study surveyed 33,391 employed U.S. adults ages 18 to 65. As in past studies, the participants answered questions about income and life satisfaction. But the study offered new insights because Killingsworth created a smartphone app that asked participants the question "How do you feel right now?" at random points throughout the day.

This captured the participants' experienced well-being, which is a measure of happiness in the moment. Another way that researchers measure happiness is through evaluative well-being, which examines the "global evaluation" people make of their lives, including general life satisfaction. The new study measured both experienced and evaluative well-being.

Credit: Killingsworth / PNAS

Unlike the 2010 study, the new research found that neither evaluative nor experienced well-being plateaued at the $75,000 income level. In fact, the results showed that both measures of well-being rose along with logarithmic income (which differs from raw income).

"This means that two households earning $20,000 and $60,000, respectively, would be expected to exhibit the same difference in well-being as two households earning $60,000 and $180,000, respectively," Killingsworth wrote. "The logarithmic relationship implies that marginal dollars do matter less the more one earns, while proportional differences in income have a constant association with well-being regardless of income."

Why does money matter?

The study couldn't offer any conclusive explanations for the money-happiness correlation, but Killingsworth suggested a few possibilities.

One is that extra money helps people reduce suffering and increase enjoyment. Another explanation centers on life control: Responses to the question "To what extent do you feel in control of your life?" accounted for 74 percent of the association between income and experienced well-being. Finally, financial insecurities, measured by participants reporting their difficulty in paying bills, accounted for 38 percent of the income-happiness association.

But while income may affect well-being more than previously thought, the new findings don't suggest you should assign more importance to money, or tie your ideas of personal success to income.

After all, "the more people equated money and success, the lower their experienced well-being was on average (P < 0.00001), and there did not appear to be any income level at which equating money and success was associated with greater experienced well-being," Killingsworth wrote.

This story originally appeared on: Big Think - Author:Stephen Johnson