More On: new york mets

Mets sign Josh Reddick to bolster outfield depth

Zack Scott’s dig at Mets players also bad look for organization

Mets rally past Nationals for skid-snapping win in Game 1 of twin bill

It’s up to Mets players to turn season around

Mets open to possibility of putting Noah Syndergaard in bullpen when he returns

This one’s personal. This one’s different. You get one first-ever hero in your life, and you hope it’s a good one. You hope that hero is the equivalent of your devotion, the equal of the admiration and the affection you invest. That isn’t automatic. Human beings are fragile. They are fallible. They can disappoint you. …

This one’s personal. This one’s different. You get one first-ever hero in your life, and you hope it’s a good one. You hope that hero is the equivalent of your devotion, the equal of the admiration and the affection you invest. That isn’t automatic. Human beings are fragile. They are fallible. They can disappoint you.

I got lucky.

Tom Seaver never disappointed me.

“The amazing thing,” my friend Art Shamsky told me a few years ago, “is that you’d be around Tom and people would always want to shake his hand and say hello and thank him for all the thrills he gave them, and he would smile and act cool, like this was the most natural thing in the world to him.”

He shook his head.

“And it was only a little later, when he was alone again, when he’d shake his head and say, simply, ‘People have been so nice to me my whole life.’ ”

Shamsky was there in the Miracle Year, of course, in 1969, when Seaver was 25-7 and struck out the world, when he became the first superstar in the history of the New York Mets, when he’d led them to a most unlikely World Series and a trip up the Canyon of Heroes, when there was always a smile on his face, when his beautiful wife, Nancy, was always on his arm.

He was 24 years old and he was going to be young forever.

“And if Tom could stay young forever,” Ron Swoboda once said, “then of course we could all stay young forever.”

It always has been important to keep the snapshots of that eternal summer close, and the years of prosperity that followed, because having Seaver as a hero meant that for as much as your heart could fill with joy watching him pitch, it could be equally broken by the way the road went after that.

There was 1977, of course, when a scowling cheapskate named M. Donald Grant exiled Seaver to Cincinnati and tried to kill the Mets all in one brilliant brushstroke of idiocy. But that wasn’t enough; 6 ½ years later, the Mets allowed him to leave a second time, this time to Chicago, this time because an otherwise competent man named Frank Cashen thought it wiser to protect a catcher named Junior Ortiz on his roster than a Franchise named Seaver.

So Seaver wouldn’t win his 300th game in Mets pinstripes but in the garish vestments of the mid-‘80s White Sox. And because there never seems to be enough ways to torture Mets fans that milestone wouldn’t happen at Shea Stadium but on the other side of the Triboro Bridge on Aug. 4, 1985 — Phil Rizzuto Day at Yankee Stadium.

But even THAT wasn’t enough: there was one more ill-fated return, early in the summer of 1987, Seaver giving it one final go in a simulated game at Shea; a reserve catcher named Barry Lyons went 6-for-6 against him and he knew that was that.

“I’ve used up all the competitive pitches in me,” he said.

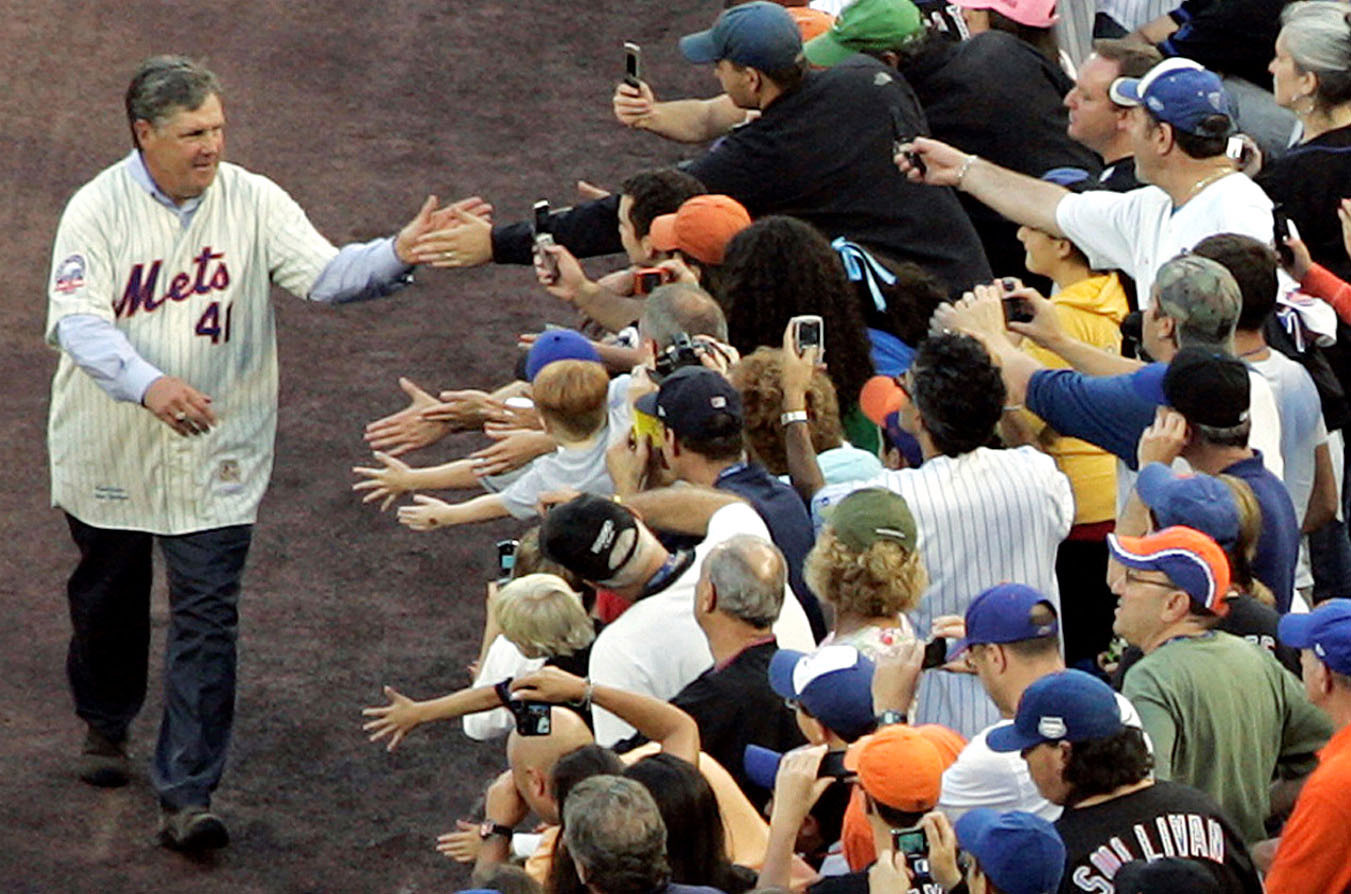

His final 33 years before his passing Monday after a battle with Lewy body dementia and COVID-19 were, in many ways, a tour through the memory banks and tear ducts of millions of Mets fans who’d latched onto him as kids. His returns to Shea, and later Citi Field, were always events, the roars for him more thunderous, more sustained, than anyone else ever heard on the banks of Flushing Bay.

I was fortunate enough to know Seaver — not well, not intimately, but enough to see that the myth was actually a good man, a grateful man, who in his most emotional public moment, as he’d cleaned out his locker in ’77, spoke of the star-fan relationship extemporaneously, and as eloquently as it can be done:

“I’ve given them a great many thrills. And they’ve been equally returned.”

The last time I spent with Seaver was one of those days that would’ve caused 8-year-old me to pass out where I stood back in 1975. We toured the Mets’ newly opened museum at Citi Field. He wept looking at pictures of Gil Hodges. He smiled watching video of young No. 41 striking out Willie Stargell.

“Get that knee smudged, son,” he said, as if he knew that a generation of Seaver acolytes had spent years scraping their own knees in emulation and tribute.

And he laughed when I asked him if it ever got too much: the adulation, the adoration, the constant stream of grown-up kids (like me) who wanted him to know how much he meant to them. Seaver thought about that for a second.

“To me,” he said, “the greatest thing anyone can ever call you is a hero, for whatever their reason. And I don’t think it’s a hardship making sure you don’t disappoint them.”

I got lucky, the way so many New York kids of the ‘60s and ‘70s got lucky.

Tom Seaver never disappointed us.