When did the first humans arise on planet Earth?

When our planet was four billion years old, big plants and animals were just starting to get bigger. The Cambrian explosion happened around this time. It was caused by the combination of multicellularity, sexual reproduction, and other advances in genetics. Over the next 500 million years, evolution went through a lot of changes. Extinction events and selection pressures made it possible for new kinds of life to come into being and grow.

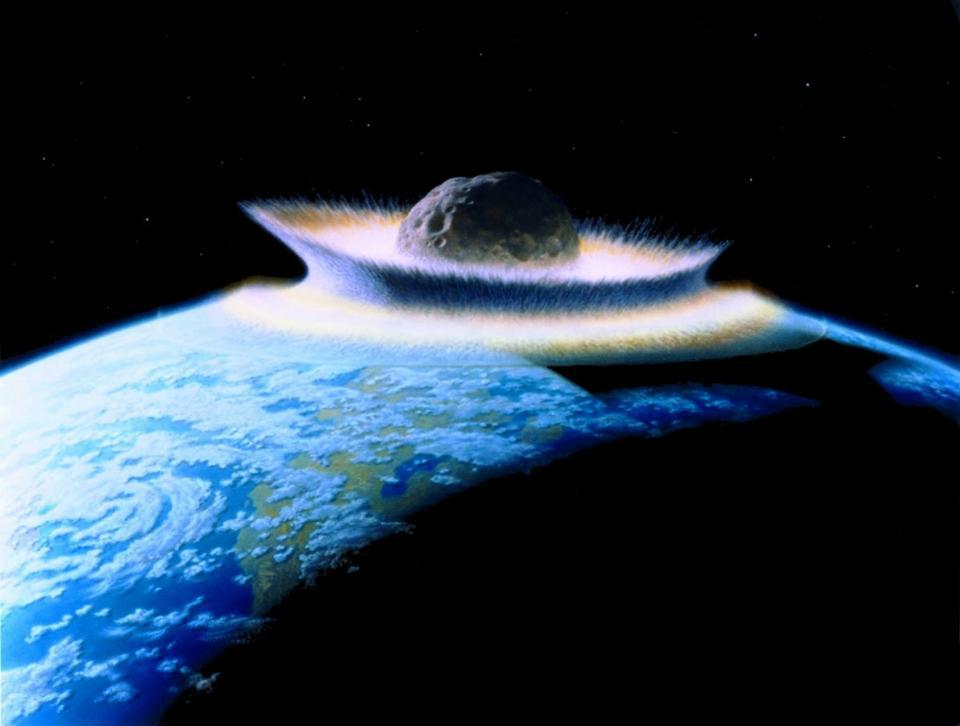

65 million years ago, a huge asteroid hit Earth and killed almost every animal that weighed more than 25 kg. This included the dinosaurs (excepting leatherback sea turtles and some crocodiles). This was Earth's most recent great mass extinction, and it left behind a lot of empty niches. After that, mammals became more important, and the first people appeared less than 1 million years ago. Here's what happened.

65 million years ago, our planet was hit by a huge asteroid that was between 5 and 10 kilometers across. It kicked up a layer of dust that fell all over the world and is now a part of the sedimentary rock on Earth. On the side of that layer that is older, there are many fossils of dinosaurs, pterosaurs, ichthyosaurs, and plesiosaurs. Before that event, there were giant reptiles, ammonites, and large groups of plants and animals, as well as small birds that could fly and small mammals that lived on land.

After that, the animals were able to keep living. Since there were no bigger animals to stop them, they grew, changed, and their numbers exploded. At the start of the Cenezoic epoch, there are a lot of primates, rodents, lagomorphs, and other kinds of mammals, like placental mammals, marsupials, and even mammals that lay eggs.

Almost immediately, the primates began diversifying even further. 63 million years ago — just 2 million years after the demise of the dinosaurs — they split into two groups.

- The dry-nosed primates, known formally as the haplorrhines, which developed into modern monkeys and apes.

- The wet-nosed primates, known as the strepsirrhines, which developed into modern lemurs and aye-ayes.

58 million years ago, another big change occurred: the haplorrhines experienced an interesting genetic split, as the first novel and unique evolutionary branch became distinct from the rest of the dry-nosed primates: the tarsier. With its enormous eyes, it was uniquely well-adapted to see at night.

Since the niche it now filled was different enough from the other groups of our ancestors, it started to change in a different way than the other cousins. This kind of split in evolution happens every so often, and it's not just found in primates.

We don't usually think much about our distant cousins and how they change after they split off from us. However, not only haplorrhines like us and our direct ancestors went through interesting stages of evolution. Mammals, birds, plants, and other living things have all changed together over the past 65 million years, just as they did before that. Changes in the environment are what drive evolution. This includes all the changes in plants and animals that happen on our planet.

55 million years ago, a sudden rise in greenhouse gases caused the average global temperature to rise quickly. This killed many deep-sea plants and animals. Because of this change, there were a lot of big holes in the ocean that needed to be filled. This made room for cetaceans, which are the big oceanic mammals.

Before 50 million years ago, some of the even-toed mammals started to change into animals that lived in the sea. Artiodactyls may have all come from the same ancestor, or they may have come about on their own. Animals like Indohyus, which lived 48 million years ago, may have been the ancestors of protocetids, which were mammals that lived in shallow water but came back to land to give birth.

About 47 million years ago, a primate called Darwinius masillae lived. The fossil Ida, which is from that time, is a great example of this. Even though this was first called a "missing link" in the evolution of humans, Ida is not a haplorrhine like us. Instead, she is a strepsirrhene, which means she is a wet-nosed primate.

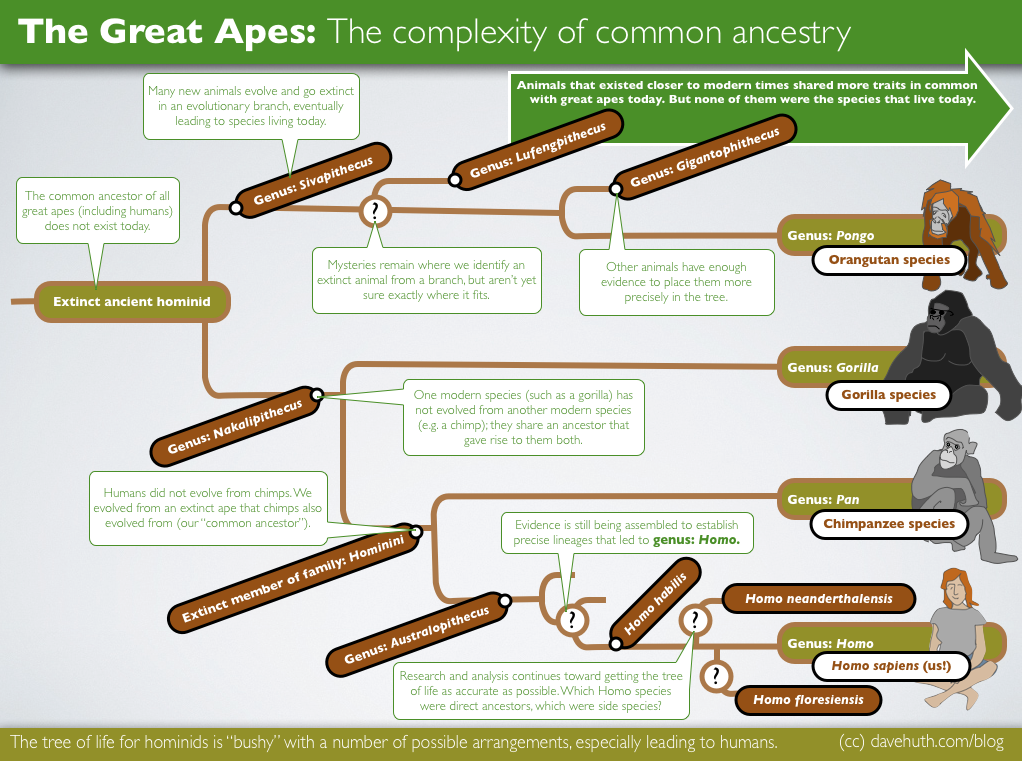

But 7 million years later, or 40 million years ago, the dry-nosed primates went through an important change: the New World monkeys split off. Old World monkeys are the ancestors of both humans and our ape ancestors. New World monkeys are the first simians (or higher primates) that evolved separately from our lineage. They went on to settle most of South America, which is still full of them today.

The Old World monkeys continue to live and do well in their niches, even though their body sizes and features are changing. Before 25 million years ago, the first apes split off from the monkeys that were still living in the Old World. The apes, who didn't have any kind of tail, went on to give rise to both the lesser and the great apes, which are close relatives of humans that still live today.

The Gibbon, a lesser ape that first appeared 18 million years ago, was the first ape to break away from the Old World monkeys.

Between 14 and 16 million years ago, the first great apes showed up, and 14 million years ago, Orang-utans split off. The other great apes stayed in Africa, while the Orang-utans moved into southern Asia. Gigantopithecus, the biggest primate ever, lived about 9 million years ago and died out only a few hundred thousand years ago.

Gorillas split off from the other great apes about 7 million years ago. They are still the largest of the primates that are still alive.

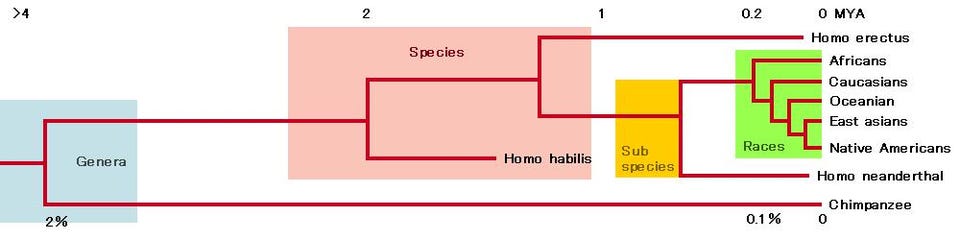

Six million years ago, the great apes split into two groups. One group became the ancestors of humans, while the other gave rise to chimpanzees and bonobos. The chimpanzee/bonobo branch stays together for another 4 million years. Our closest living relatives, the chimpanzees and bonobos, split from each other only 2 million years ago.

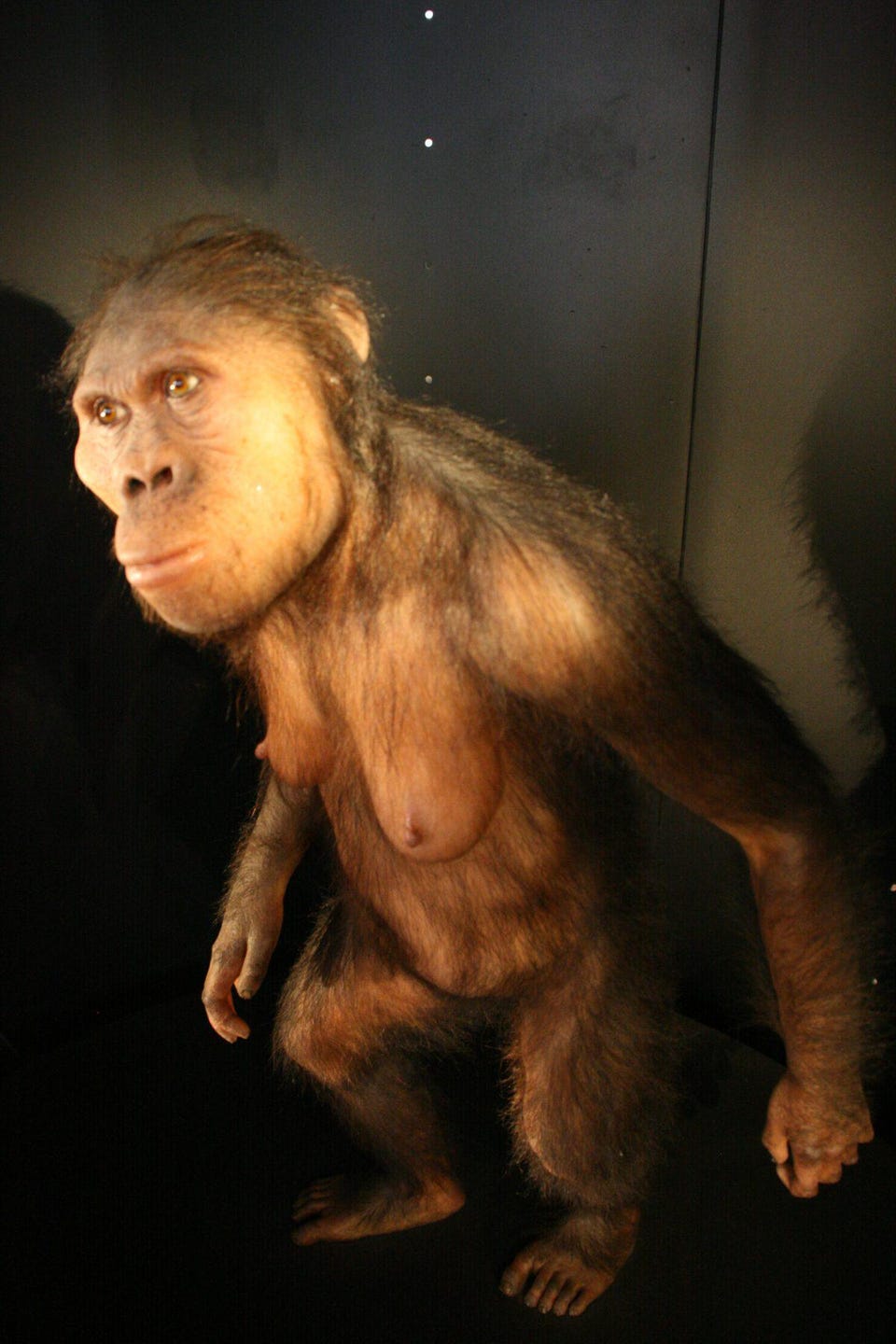

But along the path of our direct ancestors, things changed quickly and in a big way. Ardipithecus was the first ape that really walked on two legs. It lived 5.6 million years ago. Even though this is a controversial idea, Ardipithecus' hand bones show that it was a link between the earlier great apes and the later Australopithecines.

About 4 million years ago, the first Australopithecus appeared. They were the first Hominina subtribe members (a taxonomic classification more specific than family but less specific than genus).

Shortly after that, around 3.4 to 3.7 million years ago, the first signs of using stone tools show up.

A little more than 2 million years ago, when our hominid ancestors ran out of food, an important step in evolution took place. One way evolution helped us was by making our jaws stronger, which let us eat things like nuts that we wouldn't have been able to eat before. But another method also worked: our jaws got weaker and our brains got bigger, which let us get to the food.

Both groups lived for a while, but the group with bigger brains was better at adapting to changes and kept living. We think this is the way evolution led to the genus Homo, which first appeared about 2.5 million years ago. Homo habilis, also called "handy man" in everyday language, had bigger brains than Australopithecus and used tools much more often.

Homo erectus appeared about 1.9 million years ago. This human ancestor not only walked upright, but also had a much bigger brain on average than Homo habilis. Homo erectus was the first direct ancestor of humans to leave Africa and the first to use fire. Homo habilis and the last Australopithecus probably died out more than a million years ago.

New members of the genus Homo appeared all over the world, including Homo antecessor in Europe about 1.2 million years ago (which may have been an evolved habilis or erectus or an early form of heidelbergensis) and Homo heidelbergensis about 600,000 years ago. About 700,000 years ago, the first signs of cooking show up, and about 500,000 years ago, the first signs of wearing clothes show up.

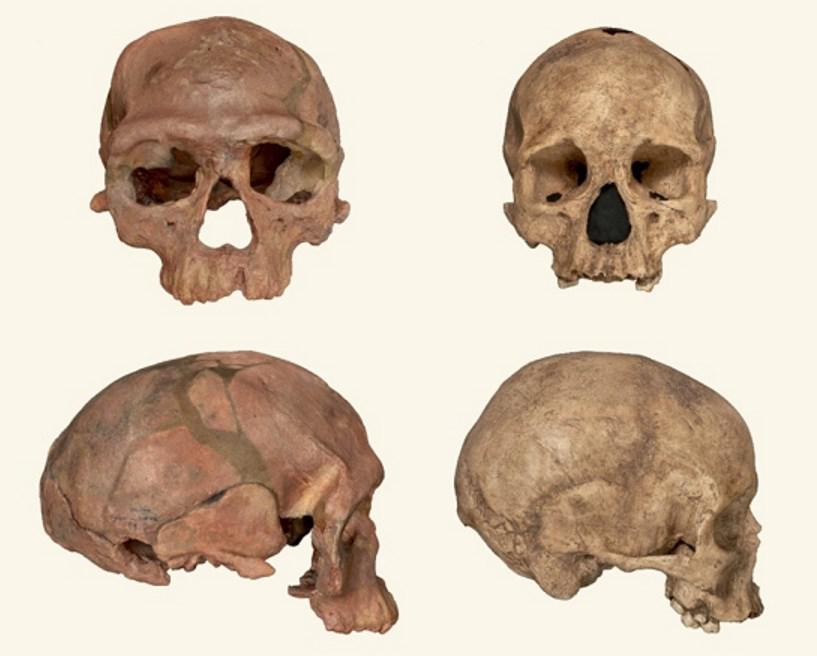

About 300,000 years ago, along with our other hominid relatives, the first Homo sapiens (anatomically modern humans) appeared. We don't know if we are directly related to Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, or Homo antecessor. However, Neanderthals, who lived about 240,000 years after us, were almost certainly related to Homo heidelbergensis. People think that modern speech started almost as soon as Homo sapiens did.

It took 13.8 billion years of the universe's history for the first people to show up, and that was only 300,000 years ago. Humans didn't exist at all for 99.998% of the time since the Big Bang. Our whole species has only been around for the last 0.002% of the Universe. Still, in that short time, we've been able to figure out the whole story of how we came to be. The story won't end with us, though, because it is still being written.