More On: Chinese virus

Trump has moved to officially withdraw the U.S. from the WHO, Joe Biden to say he will rejoin immediately if elected

Mayor Sylvester Turner will shut down the GOP Convention if it violate Chinese virus rules

US buys almost the ENTIRE world stock of remdesivir

Global COVID-19 cases surpass 10 million, half a million deaths

The Censorship about COVID-19 Data : China and the rest

History shows that national shocks—the Depression, World War II, the financial crisis—have a way of expanding the role of government in lasting ways. This one is looking like no exception. History shows that big national shocks have a way of changing the role of government in lasting ways—and any shock as big as the coronavirus …

History shows that national shocks—the Depression, World War II, the financial crisis—have a way of expanding the role of government in lasting ways. This one is looking like no exception.

History shows that big national shocks have a way of changing the role of government in lasting ways—and any shock as big as the coronavirus pandemic inevitably will alter political life and philosophies in America.

The crisis has been not just a public-health emergency requiring a sweeping response, but also the cause of the most searing economic pain since the Great Depression, summoning forth a multi-trillion-dollar government intervention into the economy.

Much of today’s new government activism will recede over time along with the virus. Yet conversations with a broad cross-section of political figures suggest there is little reason to expect a return to what had been the status quo on federal spending, or the prevailing attitude toward the proper role of government.

“The era of Ronald Reagan, that said basically the government is the enemy, is over,” said Rahm Emanuel, a moderate Democrat who served as mayor of Chicago, a member of Congress and President Obama’s first White House chief of staff.

An echo came from the other side of the political spectrum. “The era of Robert Taft, limited-government conservatism?” said Steve Bannon, President Trump’s onetime political guru, referring to the Ohio senator who fought the expansion of government programs and federal borrowing. “It’s not relevant. It’s just not relevant.”

The Great Depression produced both a bigger social safety net and a host of new government programs, World War II led to the creation of a unified Defense Department and the Cold War spawned an interstate highway system. In just the past two decades, the 9/11 terrorist attacks produced new consolidated agencies to handle homeland security and national intelligence, and the 2008 financial meltdown led to a broad range of new actions by the Federal Reserve that are being replicated and expanded now.

Today, both parties and a vast majority of voters have come together behind a broad and aggressive response at both the federal and state level, and have accepted a sea of new red ink at a time the federal budget deficit already was heading toward a trillion dollars annually.

Mr. Trump, more a populist activist than a traditional conservative, has enthusiastically backed that spending, ordered the construction of pop-up hospitals, used his authority to order companies to produce supplies, called for an additional federal infrastructure program and offered an expansive definition of presidential power, including the power to strip away regulations and bureaucracy in some instances.

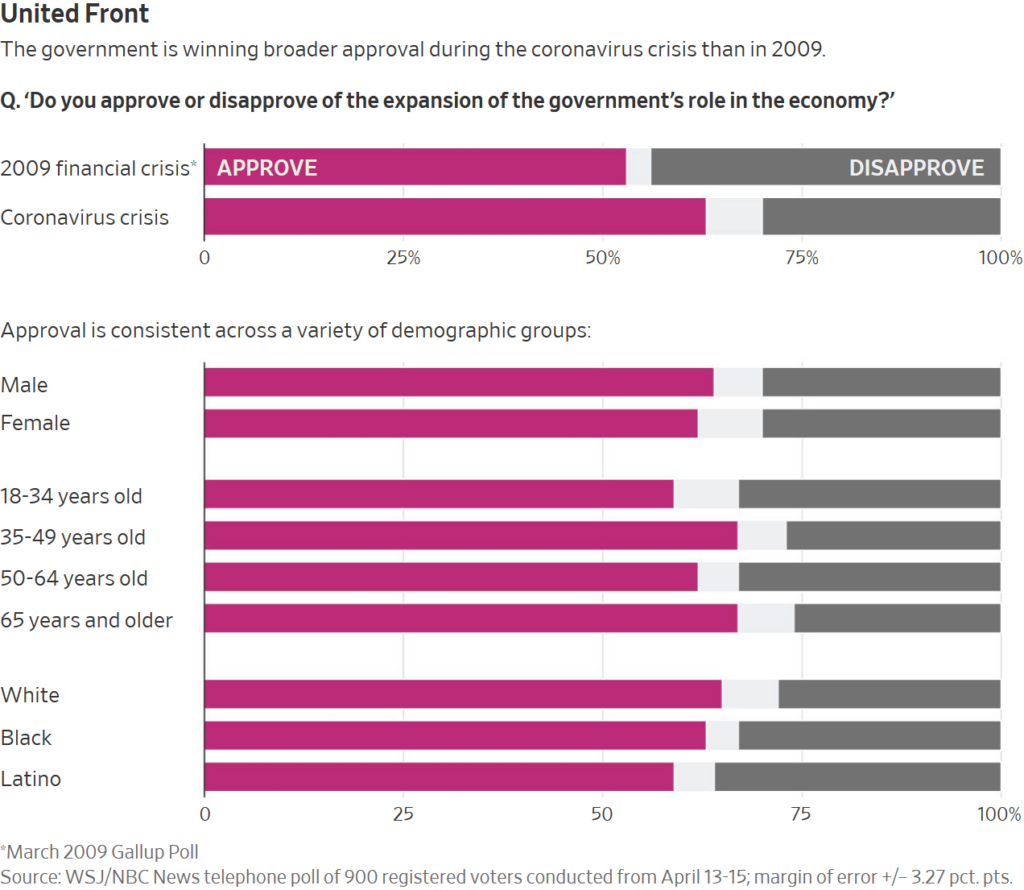

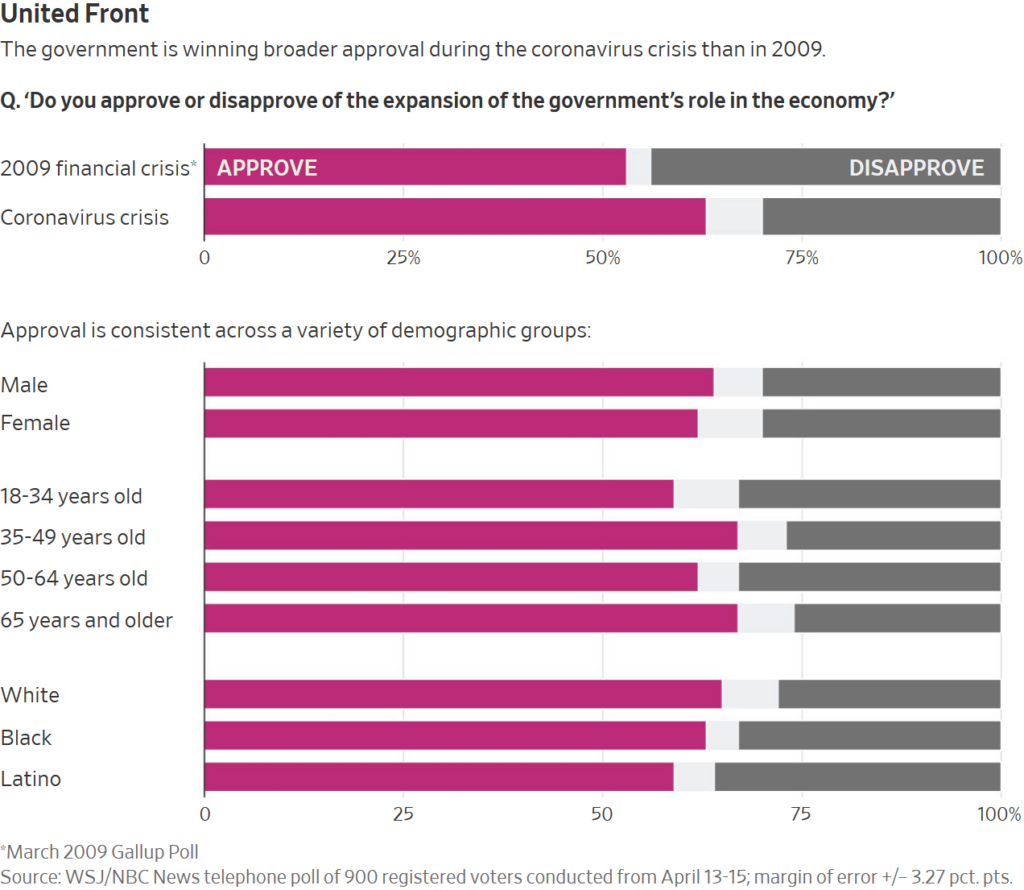

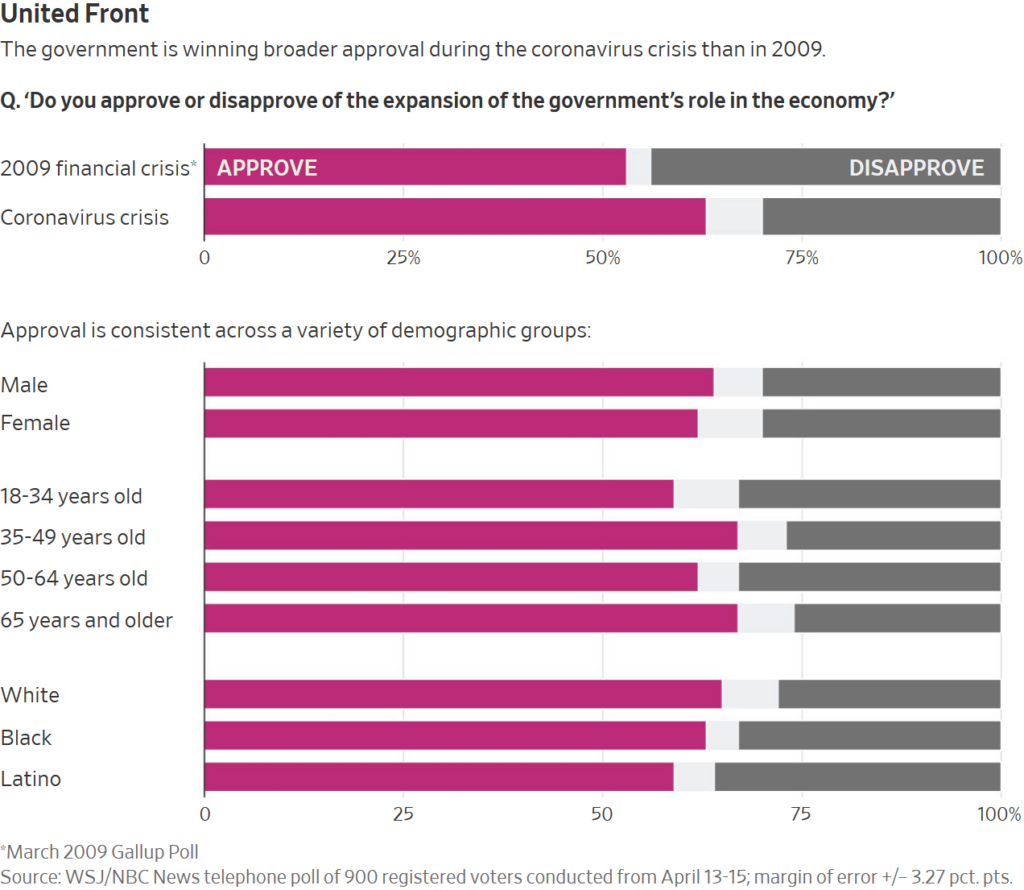

In a recent Wall Street Journal/NBC News poll, voters of both political parties said by a 2-to-1 margin that they approved of the expansion of government’s role in the economy to meet the crisis.

Oren Cass, who leads American Compass, a new organization devoted to revising conservative views on economic policy, argued that “one lesson we can and should learn from all this is that you can’t just flip a switch on strong, effective government when you need it. Just as you can’t get rid of the Defense Department in times of peace and then reconstitute it from scratch when attacked, you can’t push for the smallest possible government in normal times and expect to be ready with a competent response in an emergency.”

At the same time, while there was consensus behind government activism as the crisis struck, a loud and angry backlash now is emerging over whether the needle has moved too far, particularly on the state level. Protesters have taken to the streets in recent days, saying that political leaders, especially governors, have overstepped their authority by closing down the economy and putting American jobs and livelihoods at risk.

“We were already headed toward a conversation about whether we’re going to have a socialist country or a capitalist country,” said Jenny Beth Martin, co-founder of the Tea Party Patriots, an organization that sprang up amid grass-roots anger over government bailouts in the 2008-09 financial crisis. “When we get past the virus, we’re going to have that debate in a new way.” She and others believe a government overreaction has taken shape in recent weeks, hurting many average Americans along the way.

Similarly, Scott Reed, senior political strategist at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, is skeptical Republicans will continue to embrace big government in the same way they do now. “The size of the government is going to make Washington more and more relevant to the business community,” he said. “But long term, I think the right of center, the Republican Party, is going to want to roll that back some.”

Government spending rises amid crisis, and tends not to drop back to precrisis levels—at least not for a while. Economists call the tendency the “ratchet effect.” And while there is academic debate over its extent, a look back shows that federal spending as a percentage of the overall economy has never fallen back to its level before 9/11.

The ratchet effect may be more likely in the aftermath of this crisis because of structural problems layered over crisis spending: an aging population requiring more social services, aged infrastructure that needs updating, and the costs of servicing a historically large level of federal debt.

It is too early in this crisis to predict exactly how the size and shape of the government will be affected in the long run. For now, perhaps the clearest impact has simply been a shift in the public’s attitude toward government institutions, which have been much maligned in recent decades.

Former Iowa Democratic Gov. Tom Vilsack, Mr. Obama’s longest-serving cabinet secretary, said he expects that the “chants” he’s heard for the past 40 years about government not mattering and being the problem are likely to fade.

“This particular circumstance shows the importance of government at every level and the need for all branches to be better coordinated,” he said. “We’ve had people denigrate people in the post office and federal workers. Well, who are the people working today and putting themselves on the line?”

On the left, the crisis already is putting new energy behind calls for a nationalized health-care system. Sen. Bernie Sanders has argued that “the pandemic puts an even brighter spotlight on the shortcomings of the current corporate-run system,” and his followers are pushing the argument.

The crisis is “expediting” a move toward a more progressive Democratic Party agenda, said John Della Volpe, the polling director for RealClear Opinion Research and Harvard University’s Institute of Politics.

Others are skeptical the crisis will fuel something so dramatic as Medicare for All, the progressive proposal that got so much debate in the Democratic primary race. “Clearly, inside the party, that discussion will continue,” said Jim Messina, a Democratic strategist who ran Mr. Obama’s 2012 campaign. “I don’t think it affects the views of swing voters.”

On the Republican side, the big government response in the current crisis stands in stark contrast to the view articulated by the party’s longtime hero, the late President Reagan, in his first presidential inaugural address in 1981. Then, amid an earlier dark economic downturn, he declared: “In this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.”

Many Republicans argue that the current economic crisis is fundamentally different because it was caused by government orders to shut down businesses and public places to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, which means aggressive and expensive government action is justified to rectify the resulting problems.

“Because government action is the cause of what is going on, this action is much more acceptable in response, in Republican ranks,” said Eric Cantor, formerly the second-ranking Republican in the House.

Christopher DeMuth, distinguished fellow at the Hudson Institute, a nonpartisan think tank influential among conservatives, has argued that, by clearing away regulatory hurdles for private companies seeking answers for the virus, Mr. Trump has actually given a conservative, deregulatory twist to the bout of government activism now under way.

In the same vein, Sara Fagen, political director in President George W. Bush’s White House, said that in its response to the health crisis “government was clunky and slow, but companies quickly turned it on, so there is some argument for free enterprise.”

In addition, Republicans have been willing to embrace the recently enacted, $2 trillion economic rescue plan because a main feature was the Paycheck Protection Program, which provides relief to small businesses. Republicans consider small businesses the economic force more compatible with their political philosophy than the big banks that were the main beneficiary of the 2008 rescue package.

“Why is it that Republicans are willing to defend PPP?” asked Karl Rove, chief political strategist for Mr. Bush. “Because it serves the interests of their constituency, small businesses. Their view of a modern society is not one dominated by large corporations, but one where there is opportunity for small entrepreneurs to thrive and move up the ladder of success.”

As the country moves through and beyond the crisis, there will be a debate about whether renewed government activism, whatever its extent, ought to come at the national or state level. Governors and state governments were widely seen as more nimble in responding to the coronavirus pandemic at the outset, and have taken on an added prominence that seems likely to persist.

Traditionally, Republicans have tended to prefer a federalist approach, which seeks to move government power away from the national government in Washington and out to the governors and the states.

Mr. Trump’s sweeping declaration this month that he, as president, has “total authority” to decide when to order governors to loosen social-isolation restrictions and reopen their economies runs directly counter to that traditional conservative mind-set. Though he subsequently backtracked on trying to exercise such powers, the tone he struck was decidedly different from Mr. Reagan’s frequent invocation of the Constitution’s 10th Amendment, which reserves for the states or the people powers not explicitly granted to the federal government.

Long before this crisis struck, Mr. Trump had been moving the Republican party away from its Reagan-era embrace of traditional conservative precepts and toward a more populist view of government’s role. That populist philosophy isn’t shy about using government power, or the government’s checkbook, to the benefit of working-class Americans.

Thus, in the midst of the crisis, the Trump administration declared that the federal government would pay the coronavirus health bills of any Americans without health insurance—and reimburse health-care providers at the rates paid by the Medicare health program for the elderly. That step appeared to offer at least a glancing nod toward a Medicare for All system long advocated by the Democrats’ left wing.

Moreover, in direct contradiction to traditional Republican antipathy to deficit spending and a growing national debt, Mr. Trump has explicitly argued in favor of borrowing, at a time of low interest rates, to finance a new, $2 trillion bill to rebuild and improve the nation’s infrastructure. Even before the crisis, there was a push for a larger national effort to build out a 5G wireless network, a cause that seems even more relevant now that much of the nation’s work and learning has moved online.

Mr. Bannon argues that voters will see a powerful central government as essential as the U.S. moves into a long-term era of confrontation with China, where the coronavirus originated. A broad period of tension, he said, “is going to change the focus of government.”

In the long run, the impact of the crisis may depend on how quickly or how slowly the economy bounces back. Voters’ reaction may break not along ideological or personality lines, but rather in favor of more competent government at all levels—government that efficiently builds stockpiles of needed supplies for use in a national crisis, for instance, and responds quickly and efficiently when one strikes.

“The way the pendulum swings, the quieter, competent leaders might be more in fashion,” said nonpartisan pollster J. Ann Selzer.

By Gerald F. Seib and John McCormick