More On: Couto Misto

Couto Misto existed peacefully for seven hundred years under what we would call anarchy

People commonly believe that a society without central political authority will dissolve into chaos. But a small kingdom within Spain existed peacefully for seven hundred years under what we would call anarchy.

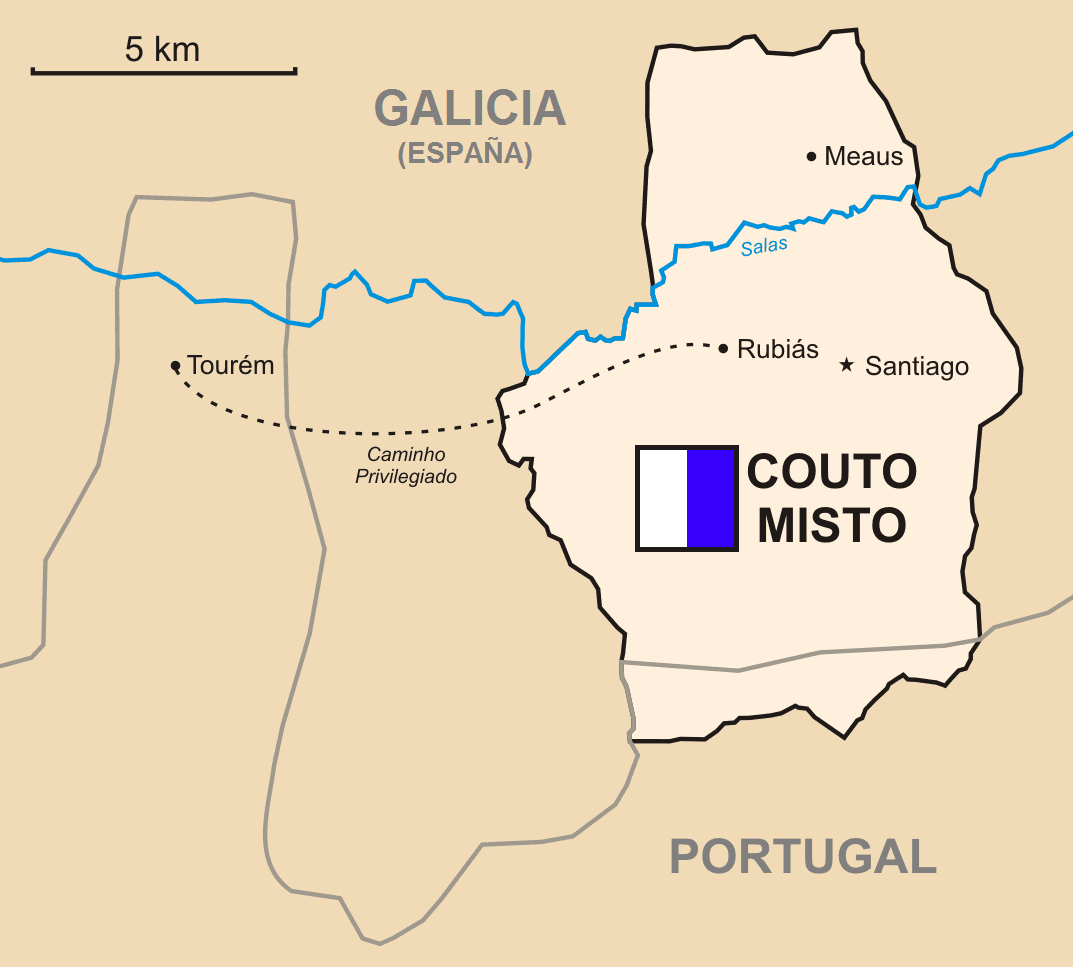

A tangible example of an anarchic order existed in Spain, in the kingdoms of Castile and Galicia, on the current border between Spain and Portugal. By "anarchy" I mean the eradication of centralized power, not the abolition of authority as understood by the left. The name of one such regime was Coto Mixto (or Couto Misto (Portuguese: Couto Misto [ˈkotu ˈmiʃtu]; Galician: Couto Mixto; Spanish: Coto Mixto). It was a tiny territory situated in the Salas River basin. From approximately 1143 to 1868, Coto Mixto's inhabitants evaded Spanish and Portuguese control. It was thirty square kilometers in size and belonged to the diocese of Orense.

According to the 1864 census, the one thousand residents of Coto Mixto did not have a monarch or a feudal lord and retained their historic privileges. Its social structures could be considered anarchic because the mayor, known as the judge, was elected by one family chief in an assembly every three years, and he was advised by three men from the region's villages. It operated similarly to a contemporary neighborhood association, in which every one or two years, one member per home elects a chairman. In addition, laws were ancient unwritten traditions and customs that were not dissimilar to the natural law.

Throughout seven centuries, they maintained historical privileges recognized by other kingdoms, such as free citizenship selection, tax exemptions, and voluntary military service. In Coto Mixto, there were no security forces, and anyone could be detained or deprived of his possessions, although locals turned over murder suspects to Spanish forces if the evidence was conclusive. They also had asylum and farming privileges, allowing them to cultivate tobacco, which was and still is a state-enforced monopoly in Spain. Thanks to the "Camio Privilegiado," a commercial route between Portugal and Spain on which no foreign authority could impose tariffs, they could have engaged in free trade.

Contrary to the assertion of statists that anarchist societies are insecure, there is no evidence that Coto Mixto's free society has a higher crime rate than Portugal or Spain. Moreover, the locals were devout Catholics who respected all traditions and worked together for the common welfare; therefore, it appears that the notion that we need the government to enforce morality and virtues is another myth. This anarchist society was finally stable for seven centuries without violence or the need for a state to maintain peace, prosperity, and stability.

After examining the merits of this regime, we must inquire as to why Coto Mixto disappeared. Queen Isabella II's liberal administration (known as Jacobin liberalism in Spain) viewed Coto Mixto as a hindrance to their homogeneity and egalitarian objectives.

In the name of national security, they launched a smear campaign against mixtos, claiming that the hundreds of people who benefited from mixtos supported smuggling and criminality. As we have seen, such claims are blatant slander, but they were sufficient for the kingdoms of Spain and Portugal to sign the Treaty of Lisbon in 1864 and divide the territory of Coto Mixto. In 1868, the locals ultimately surrendered.

There are numerous concerns regarding genuine anarchy. Could anarchy coexist with order? Yes, since it is the natural human organization system based on natural law. Could this system stand the test of time? Yes, but we must not forget that Coto Mixto persisted so long because of feudal rights and the inaction of the Spanish and Portuguese governments. Because they had more powerful armies, whenever these powers desired, they abolished all historical legal customs and liberties, just as any modern government would do if it wished to eliminate constitutional restrictions on its authority.

The utopian solution of dividing Europe into hundreds of political units in which no state is larger than Liechtenstein or the small principalities of the Holy Roman Empire will be difficult if we do not reconsider feudal rights, not as evil institutions but as a viable alternative to the increasing centralization of state power in Brussels, the United Nations, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, and the European Union. Secession is only possible if the citizens of neighboring city-states never sanction military attacks against one another. All secessionist and anarchist movements will be crushed with disproportionate force if the culture war is not won.

Coto Mixto is just one of a lengthy list of anarchic societies with some degree of order. The reader may also refer to the American West (19th century), Celtic Ireland (650–1650), the Icelandic Commonwealth (930–1262), Rhode Island (1636–48), Albemarle (1640–63), Pennsylvania (1681–90), and Cospaia (1440–1800) for additional examples. Anarchy is not unachievable.