When Tomatoes Were Held Responsible for Werewolves and Witchcraft.

No other vegetable has been as maligned as the tomato (and it is a vegetable, by order of the United States Supreme Court). We call tomatoes killers. We call them rotten. We call them ugly. We call them sad. To discover why, travel back to the 1500s, when the modest fruit first arrived on European shores (and it is a fruit, by scientific consensus). The tomato, by no fault of its own, landed in the heart of a continent-wide witchcraft scare and a tumultuous scientific community.

Thousands of Europeans (mainly women) were killed for practicing witchcraft between 1300 and 1650, in a church- and government-sanctioned mass panic known as the "witch craze" by scholars. After trials in secular and religious tribunals, women were burnt, drowned, hung, and crushed, and vigilante crowds lynched them. Dr. Ronald Hutton's examination of execution documents suggests that between 35,184 and 63,850 witches were executed through official routes, including at least 17,000 in Germany alone. Sociologist Nachman Ben-Yehuda estimates the combined death toll could have been as high as 500,000. It was a massive, concerted, prolonged crusade.

When the tomato was first imported about 1540, witch hunters were especially interested in determining the composition of flying ointment, the goo witches put on their broomsticks (or on themselves, pre-broomstick). This potent magical gunk did more than enable airborne meetings with the devil; it could also transform the witch—or her unwilling dupe—into a werewolf, as described in case studies by prolific witch-hunter Henry Boguet, who noted that witches particularly enjoyed becoming werewolves in order to attack the left sides of small children, and to stalk through cursed and withering cropland.

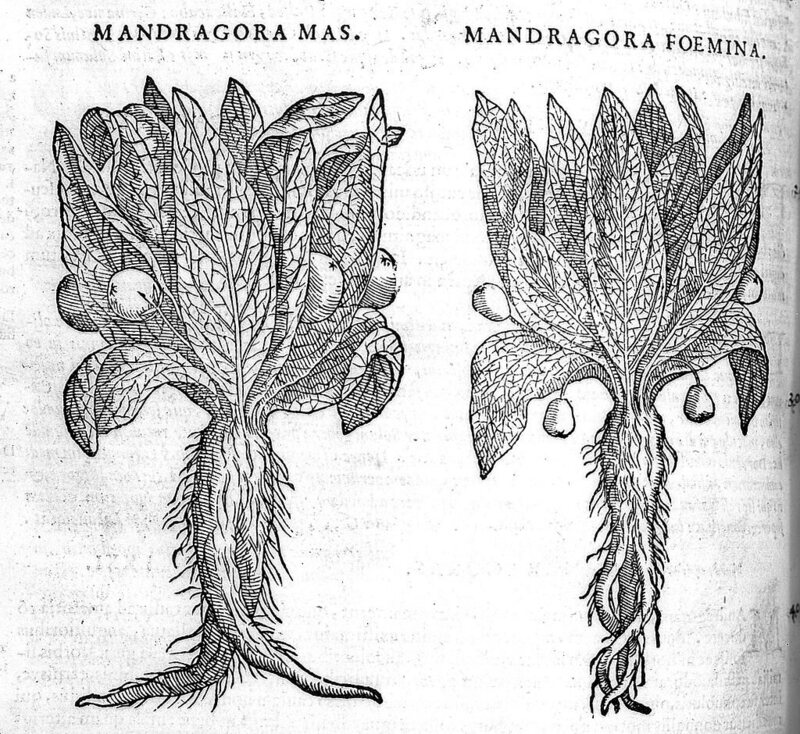

The key ingredients, recorded by the pope’s physician Andres Laguna in 1545, were agreed by consensus to be hemlock, nightshade, henbane, and mandrake—the final three of which are the tomato’s close botanical relatives. We can only hypothesize as to why any lady would have this ointment on hand in such a risky atmosphere; the best suggestions are drug addiction, atropine-based painkiller, and they didn't. Tomatoes, on the other hand, have a striking resemblance to deadly nightshade: the plants are nearly identical. And, while tomatoes were plainly edible (the Aztecs ate them), distinguishing between golden cherry tomatoes and hallucinogenic mandrake fruit is difficult.

The overlap between individuals skeptical of novel cuisines and people suspicious that an adventurous neighbor may be a devil's servant was very strong back then, as it is now. If you eat a tomato, you may change into a werewolf or be labeled a witch. Thank you, but no. Tomatoes were better left to places like Spain, where the Spanish Inquisition had proclaimed belief in witchcraft (and hence allegations of witchcraft) heretical, at least temporarily.

Even scientists, who would never believe in something as ridiculous as magic, were irritated by the tomato. Botanists depended on a thousand-year-old categorical framework developed by Galen, an Ancient Rome physician, until the Enlightenment. Naturalists were perplexed when new and unusual American plants—corn, blueberries, and chocolate—arrived. They tried to come up with techniques to disguise the new imports as old plants that might fit into the existing system. The alternative was terrifying: accepting that the great Galen had never heard of these plants would imply, as David Gentilcore describes in Pomodoro, that the ancients hadn’t known everything; that perhaps the world was in some sense unknowable; that the Garden of Eden hadn’t existed.

Given the tomato’s similarity to an existing plant—nightshade—it could have escaped the controversy. However, bits of Galen’s writings referred to plants or animals whose identities had never been nailed down, and American arrivals seemed like candidates to fill the gaps. One such mystery plant was the λυκοπέρσιον, which translates to wolf-something—maybe “wolf banisher.” It transliterates to “lycopersion,” but during the Age of Exploration was mis-transcribed as “lycopersicon”: wolf peach.

Galen describes it as a poisonous Egyptian plant with strong-smelling yellow juice and a ribbed celery-like stalk. At least as early as 1561, Italian and Spanish botanists, no doubt aware of witchfinders’ werewolf suspicions, were kicking around the idea that the wolf peach and the tomato could be one and the same.

This categorisation sparked debate. Not only was the tomato not toxic, but it also couldn't have come from ancient Egypt or Peru, as scientist Costanzo Felici noted in 1569. Tomatoes were known as golden apples, Peruvian apples, love apples, wolf peaches, and other names as seed traffickers waited for the vernacular to take hold.

The debate was eventually settled by Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, Louis XIV’s botanist, who accepted the tomato’s werewolfish “lycopersicum” name in his hugely influential three-volume 1694 Elemens de Botanique . (Surely you’ve noticed that “lycopene” sounds an awful lot like “lycanthropy.”) He went so far as to call the tomato the “Lycopersicum rubro non striato“—the red wolf’s peach without ribs.

Tournefort's book was conclusive, and his description matched prevailing notions, particularly in England, where physicians had disregarded the tomato as impracticable. Though tomatoes might "coole and relieve the heate and thirst of the torrid stomaches" in locations like Spain, Italy, and the Caribbean, England was already damp enough, according to James I's pharmacist John Parkinson. You'd be on the wrong side of the medieval equivalent of "fuel a fever; starve a cold" if you ate tomatoes in a chilly, wet area.

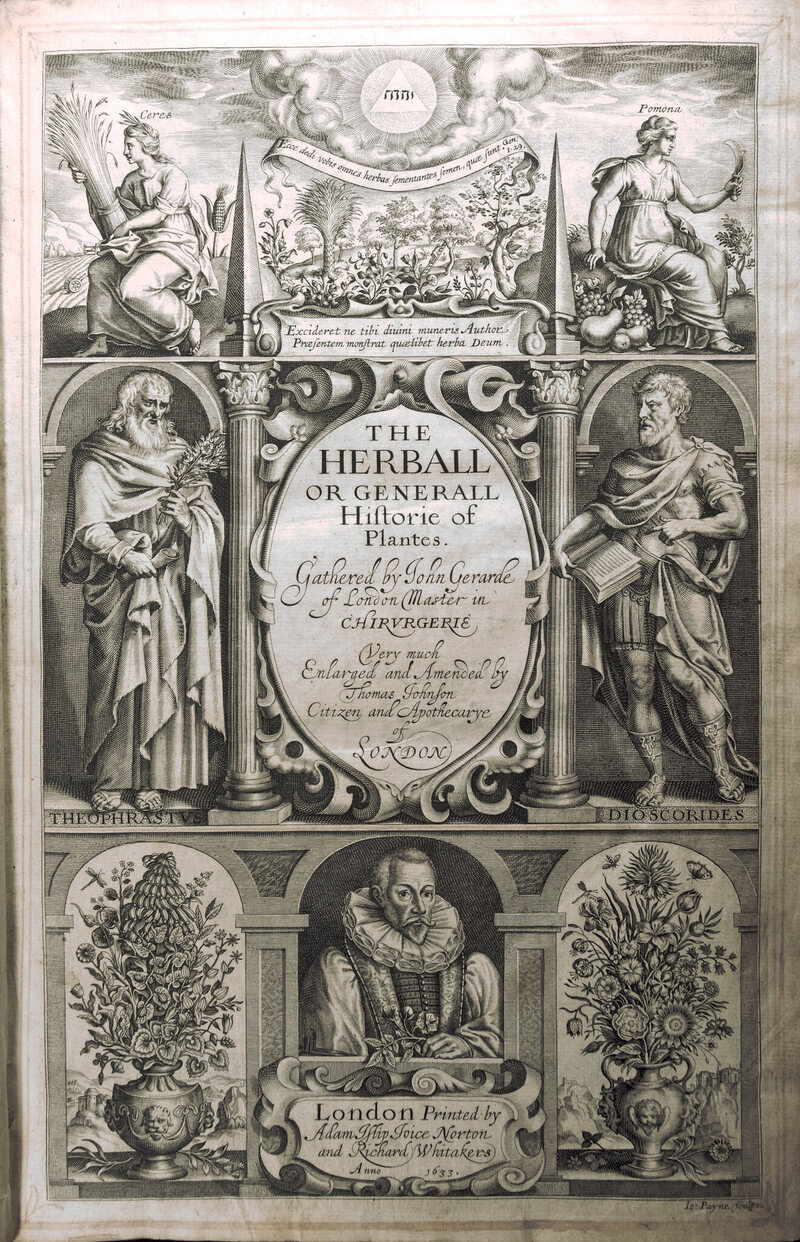

English barber/surgeon John Gerard had gone so far as to say tomatoes were “corrupt” in his 1597 Generall Historie of Plantes. “Rank and stinking,” he clarified, in case a reader was tempted by the Spanish and Italian recipes he included (fried with salt and pepper, or eaten raw with vinegar).

Much of the English population agreed, as did their descendants in what would become New England. Tomatoes were pretty, but gross and just maybe satanic even according to scientists. Adventurous eaters like Thomas Jefferson were welcome to partake, but the rest of us were better off not risking our stomachs. A contingent of English emigrants in America rejected tomatoes all the way up to 1860, when the U.S. Civil War finally mainstreamed tomato-eating—an aversion that gave rise to the medical shorthand “the tomato effect,” a description of effective therapies avoided for cultural reasons.

That's not the same as a widespread idea that tomatoes were harmful, which very certainly never happened. In his investigation of pre-1860 American literature, Andrew Smith, author of The Tomato in America, found just three allusions to tomato deadliness—and in all of them, the writers swore they were not concerned. The most famous anti-tomato lecturer in the United States was Dio Lewis, a Harvard-trained doctor who spent the 1850s blaming tomatoes for everything from bleeding gums to hemorrhoids, claiming that tomatoes' therapeutic qualities were so potent that it was easy to overdose. For the most part, the people who didn’t eat tomatoes just didn’t like them, in the same way most of us don’t make dandelions and ants a staple of our diets.

Facts, on the other hand, find it difficult to disprove a long-held belief. One modern urban legend links the tomato to a rash of lead poisoning, claiming that acidic tomatoes leeched lead from pewter dinnerware to drive 16th-century aristocrats insane. However, tomatoes aren't acidic enough, pewter dishes were never common enough, and lead poisoning accumulates too slowly to be linked to a specific meal. Colonel Robert Gibbon Johnson startled a throng in Salem, New Jersey, with his heroic ability to eat a basket of tomatoes and survive, according to another popular story refuted by Joan R. Calahan in 50 Health Scares That Fizzled. There’s even a fabricated story that George Washington’s chef tried to poison him with tomatoes.

More recently, when NASA distributed tomato seeds that had been to orbit, the L.A. Times freaked out about the imagined potential for poisonous mutations, and the panic went international. When NASA did the same with basil, nobody cared.

A lawyer from my hometown of Winchester, Massachusetts told me a few years ago that there was a law on the books banning tomato gardens—an artifact of early 20th century anti-Italian racism, meant to keep the neighborhood cleanly Anglo-Saxon. A search through the town clerk’s annual reports from the town’s founding to the present makes it clear no such bylaw ever existed. But my lawyer believed it did, just as many law blogs happily (and inaccurately) report that the General Laws of Massachusetts forbid putting tomatoes in chowder.

My lawyer didn’t realize she was repeating a werewolf myth, done up in sheep’s clothing. It slotted Massachusetts zoning codes into an older story of Puritan sumptuary legislation which regulated minute personal behaviors and set the stage for the Salem Witch Trials, and it replaced werewolves with southern Italian immigrants—who were, according to bigots in the early 1900s, dangerously swarthy, overly sexual, unpredictably violent, and presumably slavering.

The thing that didn’t change was tomatoes. With tomatoes, we made up our minds a long time ago.